Scraps of notes

Initially impressed with ChatGPT

As a last resort, I try ChatGPT haha:

ChatGPT link- https://chat.openai.com/chat/1a2694aa-d446-46b0-a1dd-f40d24377efb

ChatGPT lists several reasons for why shebangs might be preferred over file extensions, including:

- using a shebang instead of a file extension means that you can interpret multiple files with different extensions using the same interpreter, if each file has the same shebang.

- relying on file extensions means you can’t open a file if its file extension isn’t known to be associated with a given application, i.e. it isn’t standard.

- relying on the shebang allows you to execute a file using different interpreters, depending on the environment, which might only be known at runtime.

While we don’t seem to be relying on any of these facts in the case of RBENV, each point makes sense in a more general sense.

Aside- using ChatGPT as a last resort

Sometimes I find that the questions I want to ask aren’t a good fit for StackOverflow, which has a very specific format that they want you to use when asking your questions. This might be because my question takes the form of “What are the pros and cons of X?”, which can be interpreted as being opinion-based. Or they might take the form of “Why was X originally done in Y way?”, which is how my question above was interpreted. StackOverflow wants questions that are likely to have objective, clear-cut answers. With other types of questions, there didn’t use to be a great alternative. Quora would have been the closest thing that I could think of, but I’d never ask a question on their because their interface has way too many ads, and also the quality of answers is just too low.

I’m starting to think that ChatGPT might be a decent alternative. It’s not perfect by any means, but the answers I’ve pulled from it so far have been detailed and appear to be directionally accurate. It’s still important to verify whether the specific claims it makes are actually correct (as I’ll illustrate in the next aside), but I feel like that’s something we should be doing anyway, even with answers from humans. I plan on using ChatGPT as a backstop if I get stuck on subsequent questions while writing this post, if only to give me ideas for what directions to look in when I get stuck.

Getting burned by ChatGPT

So once again, I turned to ChatGPT. This time the answer it gave me may have been misleading. The question I asked was:

In a UNIX environment, why aren't new files executable by the creator of the file until you run the `chmod`

command? Shouldn't the file's creator automatically have the ability to execute the file?

And the answer it gave was:

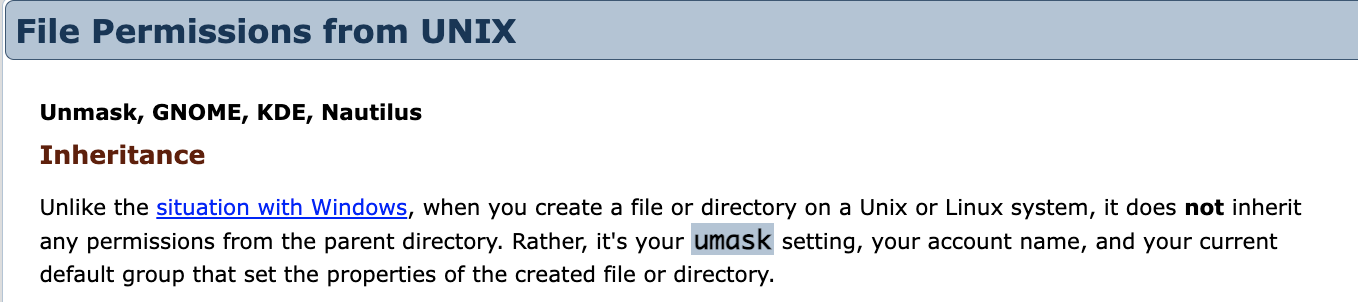

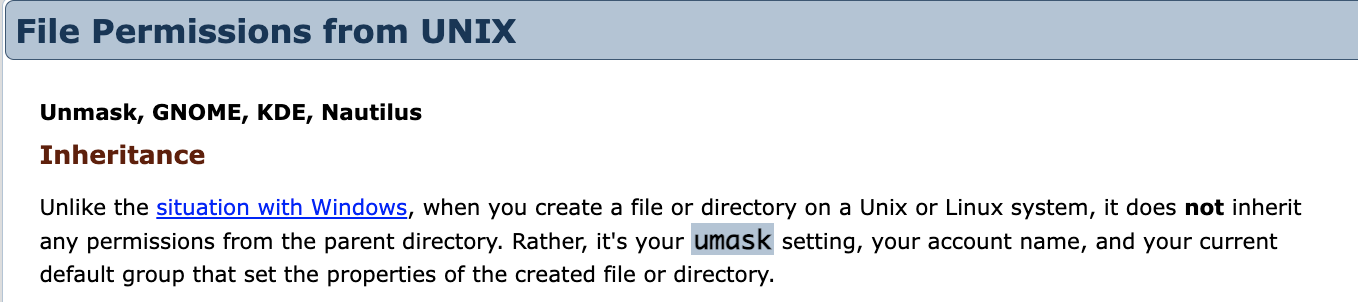

I wanted to verify the statement When a new file is created, it inherits the default permissions of the directory it was created in..., so I did an experiment. I made a directory, verified that its permissions were such that the user who created it could “execute” it, and then created a file inside that directory. But that file was not, by default, executable by its creator. That implies the ChatGPT statement was incorrect. So I Googled do unix files inherit the permissions of a directory, and got this link as the first result:

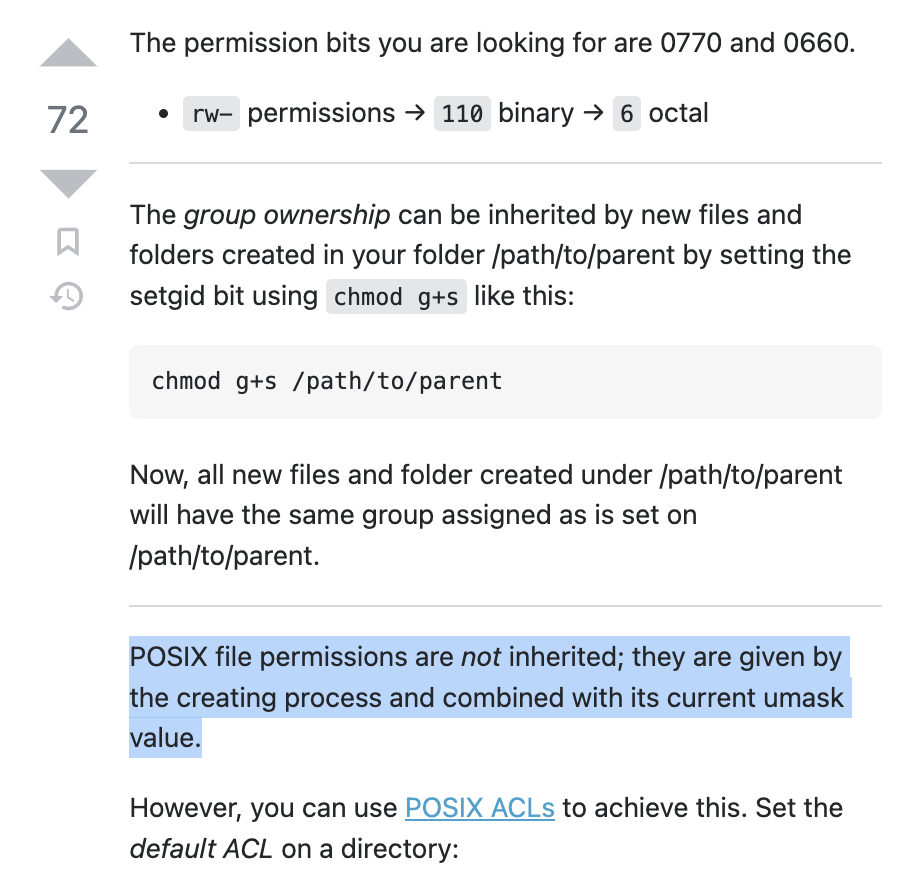

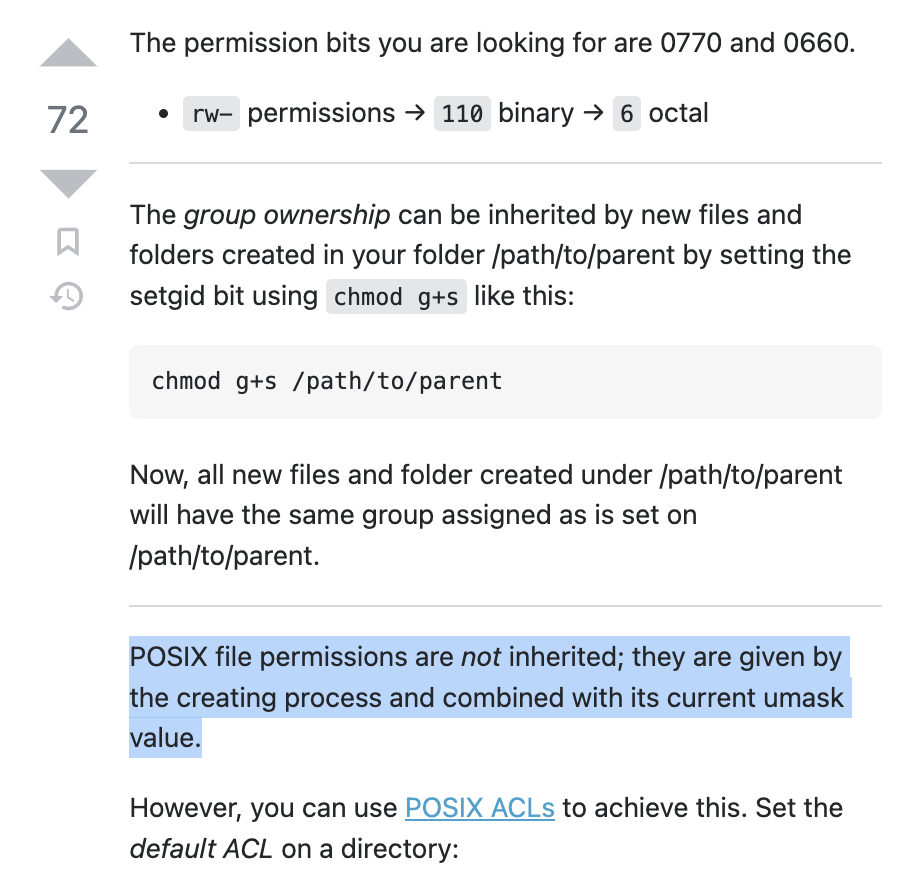

This is confirmed by this StackOverflow post:

So lesson learned- we can’t trust ChatGPT implicitly.

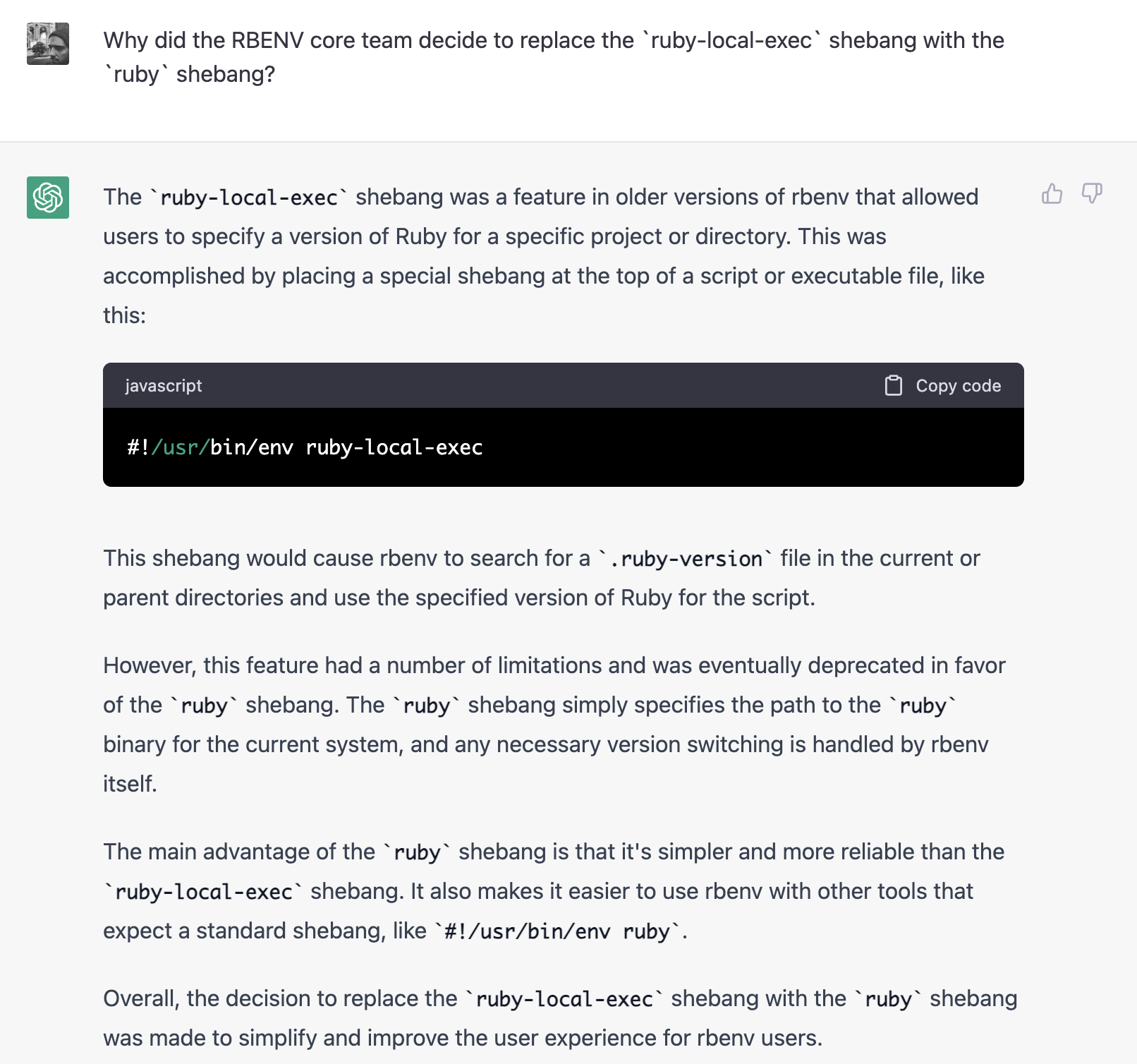

Using ChatGPT for help

As an experiment, I try asking ChatGPT for confirmation of this theory:

ChatGPT says that the newer ruby shebang is simpler, more reliable, and more portable than the old ruby-local-exec shebang. Though I don’t have any non-AI-generated evidence to support this, it seems like a plausible explanation.

A warning- getting burned by ChatGPT

I don’t want to imply that ChatGPT is a good resource to use in all cases. It definitely pays to verify any claims it makes.

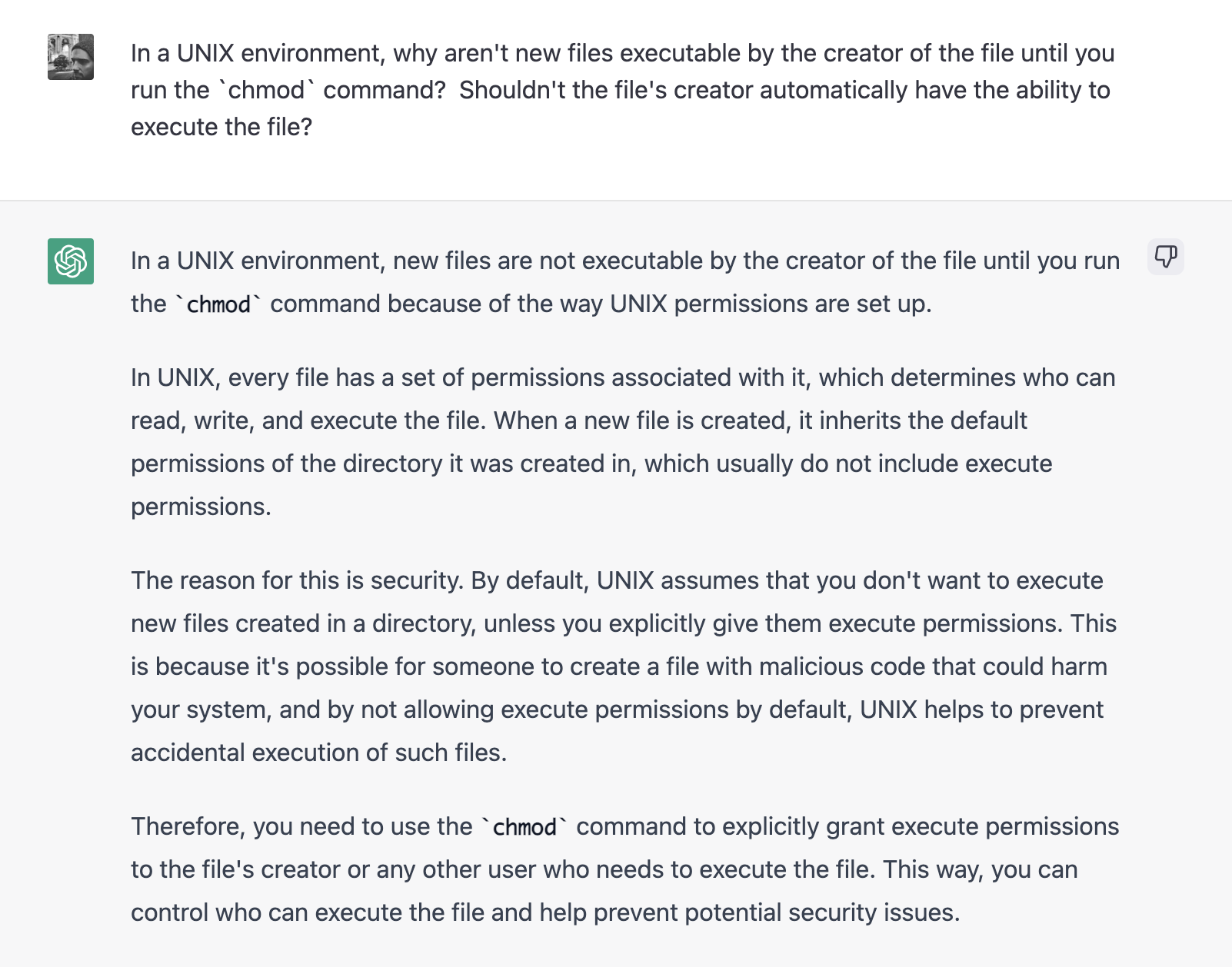

For example, when I was trying to figure out why files aren’t executable-by-default by their creator, I hit a dead end where I couldn’t find an authoritative answer online. So once again, I turned to ChatGPT. This time the answer it gave me was misleading. The question I asked was:

In a UNIX environment, why aren't new files executable by the creator of the file until you run the `chmod`

command? Shouldn't the file's creator automatically have the ability to execute the file?

And the answer it gave was:

The answer is partially correct (the goal of the policy is in fact to prevent a malicious user from executing code which could harm your system). But I wanted to verify the statement When a new file is created, it inherits the default permissions of the directory it was created in....

So I did an experiment. I made a directory and verified that its permissions were such that the user who created it could “execute” it:

$ mkdir foo

$ chmod +x foo

$ ls -l

...

drwxr-xr-x 3 myusername staff 96 Mar 6 08:43 foo

...

Then I created a file inside that directory. But that file was not, by default, executable by its creator:

$ touch foo/bar

$ ls -l foo

total 0

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 0 Mar 6 08:43 bar

This implies that the foo/bar file did not inherit its permissions from its parent directory, and that the ChatGPT statement was incorrect.

For added confirmation, I Googled do unix files inherit the permissions of a directory, and got this link as the first result:

This is confirmed by this StackOverflow post:

So lesson learned- we can’t trust ChatGPT implicitly.

How was the if-block an improvement on the old solution?

Prior to this change, did RBENV use the Ruby version in the directory from which it was run, regardless of what the Ruby version was in the target directory? To find out, roll back my RBENV and do an experiment.

I cd into my RBENV installation directory (i.e. ~/.rbenv), and verify that it is a git repository by running ls -la and searching for the .git hidden directory. Then I get the commit SHA from this link, which I see is SHA e0b8938fef05dd6d08322e113015c51e79c70291. I then run git checkout e0b8938fef05dd6d08322e113015c51e79c70291 to roll back my installed version to the commit which introduced this change.

Next, in my scratch directory (~/Workspace/OpenSource), I open a new terminal tab. This way I’m still in my same directory, but opening the new tab caused my ~/.zshrc (where I invoke rbenv init) to be re-run. This ensures I’m now using the version of RBENV that I just checked out (i.e. the version corresponding to SHA e0b8938fef05dd6d08322e113015c51e79c70291).

I then create two directories in my scratch directory- one named foo/ and one named bar/. I create a .rbenv-version file inside each directory- one set to 3.0.0 in foo/ and the other set to 2.7.5 in bar/. I then create a file named script, which I chmod +x so it’s executable. The file looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

ruby_version = `rbenv version`

puts "Ruby version: #{ruby_version}"

The \ backtick symbols surrounding rbenv version mean that we will run the rbenv version terminal command, and store the results in the variable named ruby_version`. This process is sometimes called shelling out to a sub-process.

I then copy the above script file from foo/ into bar/, so an identical file exists in each new directory. When I run ./script from within foo/, followed by ../bar/script (also from within foo/), I see:

~/Workspace/OpenSource/foo () $ ./script

Ruby version: 3.0.0 (set by /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/foo/.rbenv-version)

~/Workspace/OpenSource/foo () $ ../bar/script

Ruby version: 2.7.5 (set by /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/bar/.rbenv-version)

Next, back in the ~/.rbenv/ directory, I check out the commit before the one which introduced this change:

$ git co e0b8938fef05dd6d08322e113015c51e79c70291~

Previous HEAD position was e0b8938 Merge pull request #299 from sstephenson/automatic-local-exec

HEAD is now at 811ca05 Run `hash -r` after `rbenv rehash` when shell integration is enabled

Then, back in my foo/ directory, I open a new terminal tab again. Lastly, when I re-run my two scripts, this time I see:

$ ./script

Ruby version: 2.7.5 (set by RBENV_VERSION environment variable)

~/Workspace/OpenSource/foo () $ ../bar/script

Ruby version: 2.7.5 (set by RBENV_VERSION environment variable)

~/Workspace/OpenSource/foo () $

This time, the version numbers are the same- 2.7.5! Also, the source of the versions has changed- previously, along with the version number, we saw (set by /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/bar/.rbenv-version) in the output. This time, we see (set by RBENV_VERSION environment variable). So in both cases, the .rbenv-version file was not being used to set the version.

Extra credit: the ruby-local-exec shebang

There’s something here I still don’t understand, specifically that 2nd sentence in the description of PR # 299:

It should, in effect, remove the need for the ruby-local-exec shebang line.

It sounds like there was a previous attempt to solve the problem of setting RBENV_DIR which involved a special type of shebang, called ruby-local-exec. That makes me wonder:

- How did

ruby-local-execoriginally work? - Why did the core team feel the need to replace it? What was wrong with it?

- Why was our adding of the

if-block an improvement on that old strategy?

Digging into git history can be like pulling a sweater thread. For every question you answer, you find yourself asking two more. That’s what makes “grokking a codebase” such a slippery task- it’s never truly complete.

That said, we’ve succeeded in our goal of understanding what the if-block does. So if you want to skip this section, I wouldn’t blame you. But if you want to keep pulling on this thread with me, read on.

Looking for ruby-local-exec

I suspect that ruby-local-exec is a file. After all, the interpreters that shebangs use (such as the Bash in #!/usr/bin/env bash or the ruby in #!/usr/bin/env ruby) are just executable files, so ruby-local-exec might be a file too.

If it is a file, there must have been a git commit somewhere which introduced the file. Maybe we can use the same strategy here that we used with the if-block above.

Since our original Github issue said that the need for the ruby-local-exec shebang had been removed, I suspect this file no longer exists in the codebase. I run find . -name ruby-local-exec and no results appear, so that seems to check out. This means I have to search Github for an older version of the repository which contains the file.

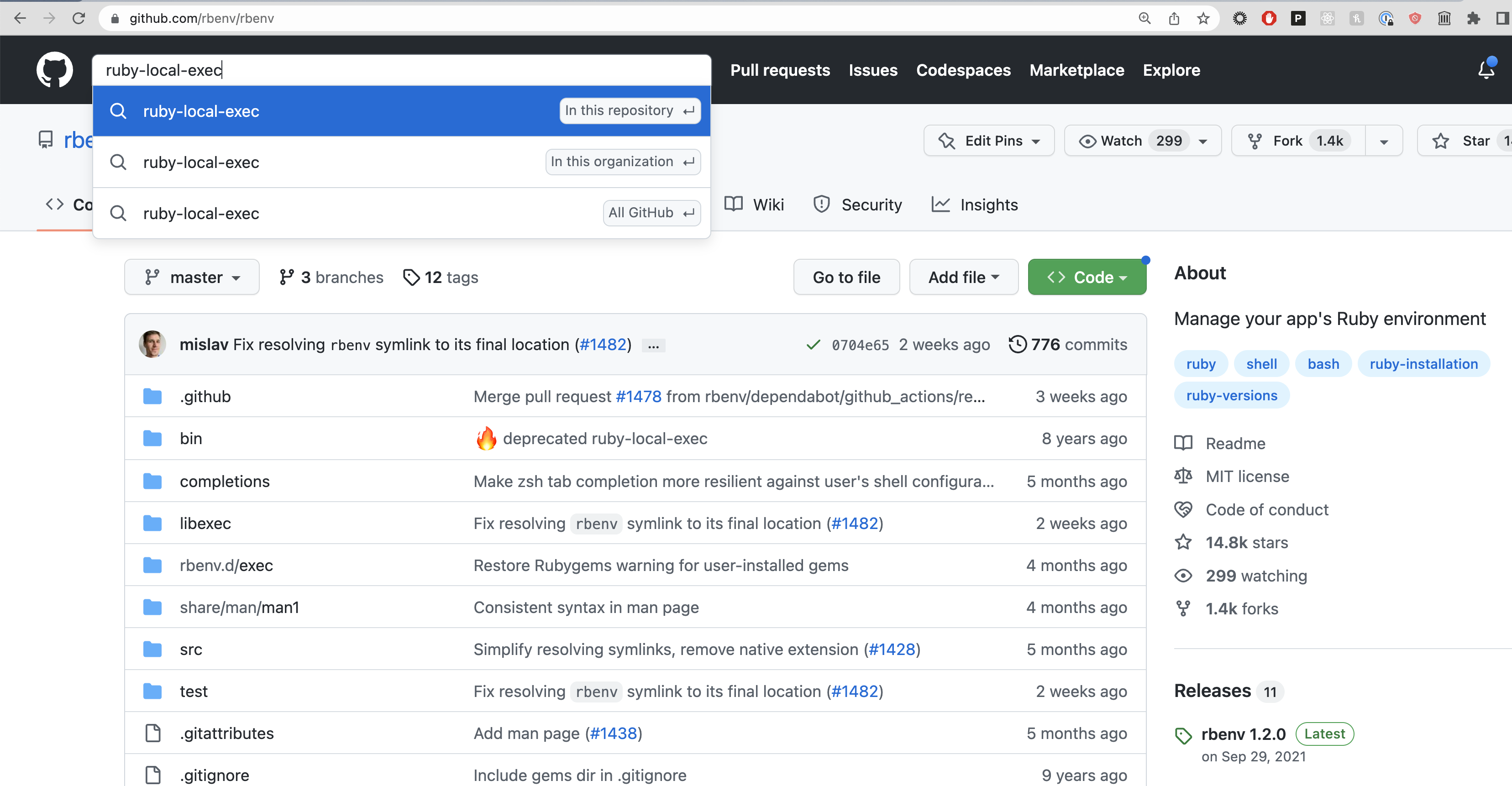

I type “ruby-local-exec” in Github’s search field while inside the Github repository (i.e. while my browser is pointed to https://github.com/rbenv/rbenv). When I do this, the “In this repository” option appears in a dropdown, and I select that.

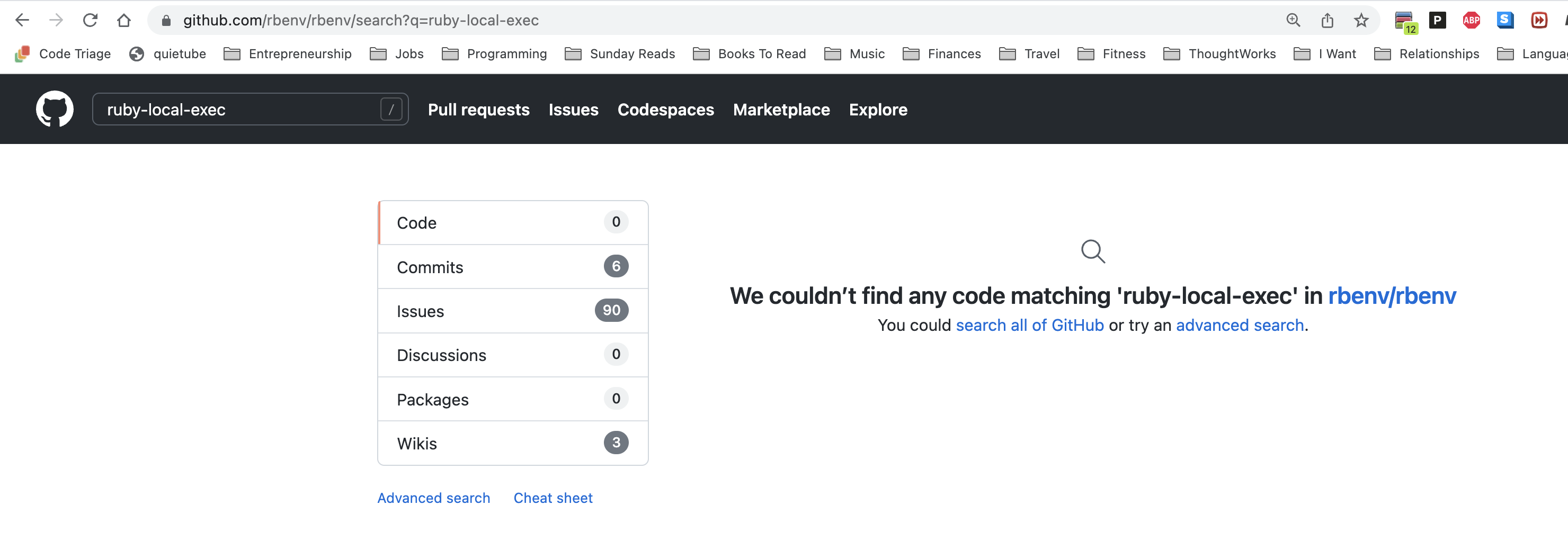

I’m taken to a search results page, which (among other things) indicates that Github found 6 commits with this string present:

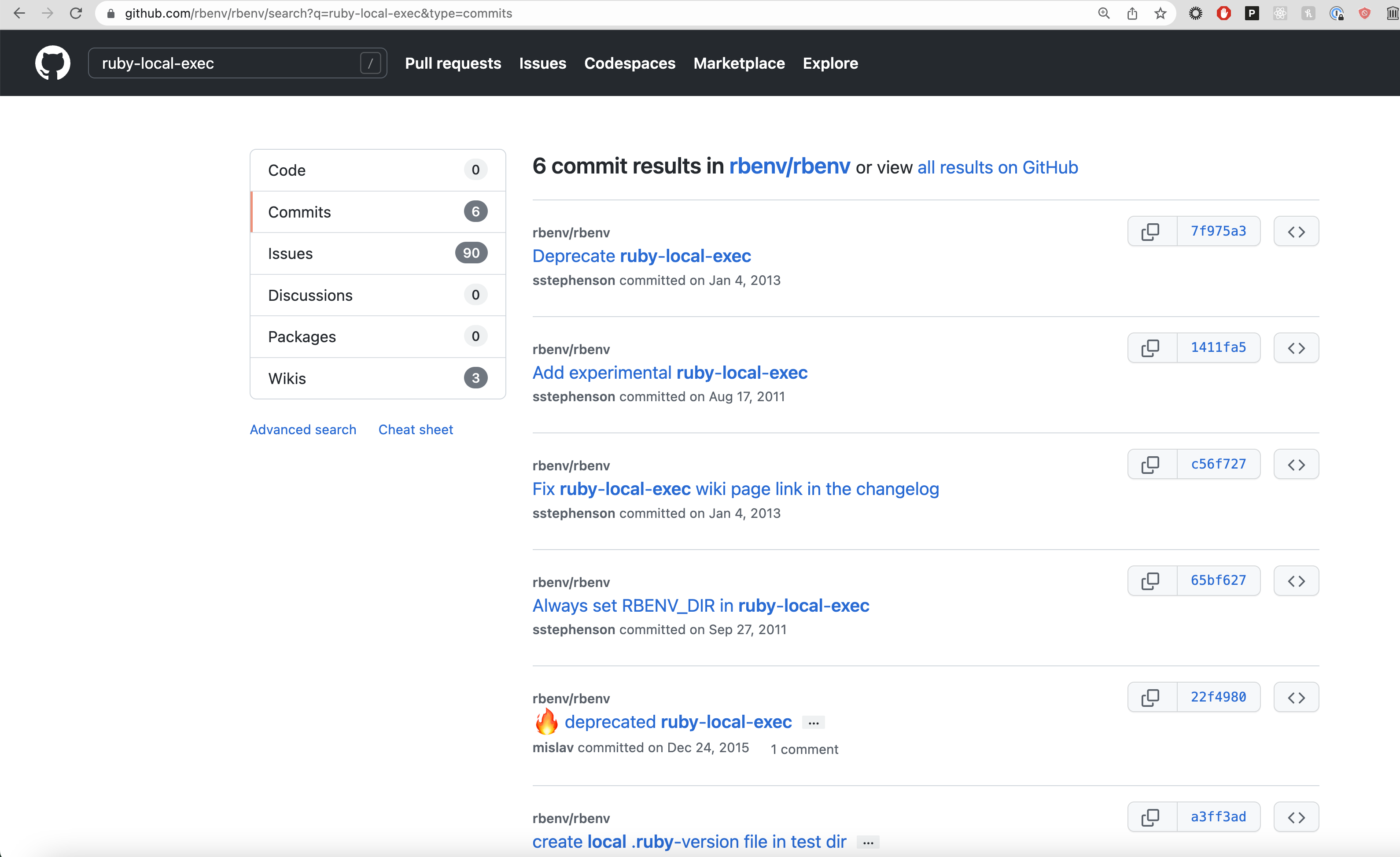

I click on “Commits” to see which commits those were. From there, I see a list of git commits, along with their commit messages:

The commit labeled “Add experimental ruby-local-exec” looks promising, so I click on that.

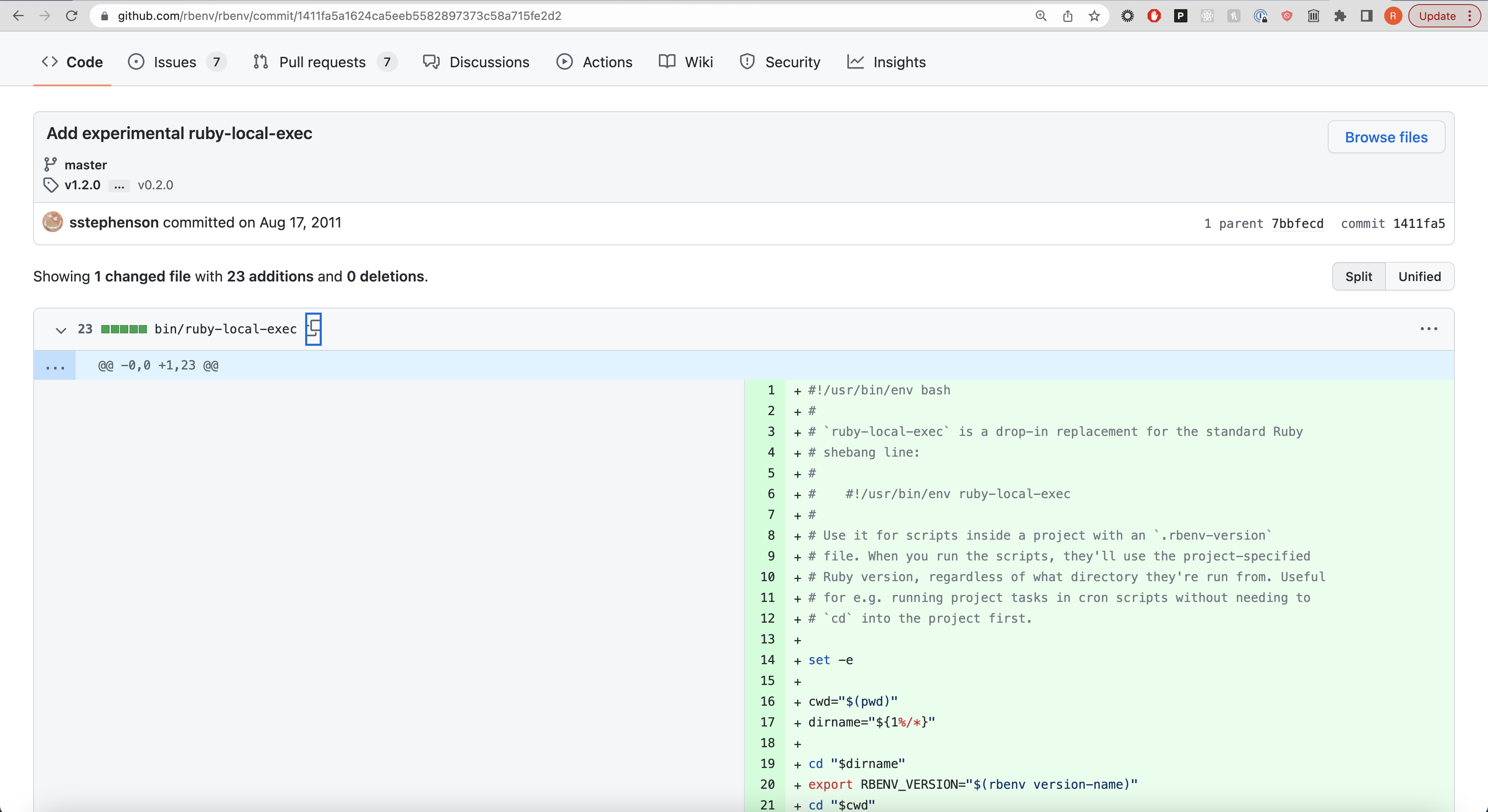

From there, I’m taken to a list of files, which (in the case of this PR) is just one file- the one we’re looking for (bin/ruby-local-exec):

Great, so we finally have confirmation that ruby-local-exec was indeed a file at some point.

How did the ruby-local-exec file work?

Now that we know the file existed, we can read its code to answer this question.

However, we have to pick which version of the file to read, because it appears that the code underwent some changes over its lifetime. When the file was first committed, it looked like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

#

# `ruby-local-exec` is a drop-in replacement for the standard Ruby

# shebang line:

#

# #!/usr/bin/env ruby-local-exec

#

# Use it for scripts inside a project with an `.rbenv-version`

# file. When you run the scripts, they'll use the project-specified

# Ruby version, regardless of what directory they're run from. Useful

# for e.g. running project tasks in cron scripts without needing to

# `cd` into the project first.

set -e

cwd="$(pwd)"

dirname="${1%/*}"

cd "$dirname"

export RBENV_VERSION="$(rbenv version-name)"

cd "$cwd"

exec ruby "$@"

And by the time the if-block which replaced it was introduced, it looked like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

#

# `ruby-local-exec` is a drop-in replacement for the standard Ruby

# shebang line:

#

# #!/usr/bin/env ruby-local-exec

#

# Use it for scripts inside a project with an `.rbenv-version`

# file. When you run the scripts, they'll use the project-specified

# Ruby version, regardless of what directory they're run from. Useful

# for e.g. running project tasks in cron scripts without needing to

# `cd` into the project first.

set -e

export RBENV_DIR="${1%/*}"

exec ruby "$@"

If our goal is to understand the need for the introduction of the if-block, then we should examine the state of the code just before that block was introduced. That will be the most relevant version of the file, for our purposes.

The file is pretty short, so let’s quickly read through each line, as we did with the shim file. I’ll leave the parsing of the file’s original version as an exercise for the reader.

The first line is:

set -e

We’ve seen this command before, so we know what that does- it tells Bash to exit immediately when it encounters an error.

Next line of code is:

export RBENV_DIR="${1%/*}"

We’re familiar with this parameter expansion pattern already. It takes the first argument and shaves off the filename, leaving just the directory path to be stored in RBENV_DIR. If we echo the value of RBENV_DIR when running our foo/foo script…

set -e

export RBENV_DIR="${1%/*}"

echo "RBENV_DIR: $RBENV_DIR"

exec ruby "$@"

…we see:

$ ./foo/foo

RBENV_DIR: ./foo

Hello world

Next and last line of code:

exec ruby "$@"

This just runs our ruby shim, passing any arguments along with it.

How was the if-block an improvement over ruby-local-exec?

While trying to answer this question,

Why the switch from .rbenv-version to .ruby-version?

The discussion in PR 298 references a file named .rbenv-version, which is of course different from the .ruby-version file we’ve previously discussed. My guess is that, at some point, the RBENV core team switched from a naming convention of .rbenv-version to .ruby-version, in order to be more inter-operable with other Ruby version managers.

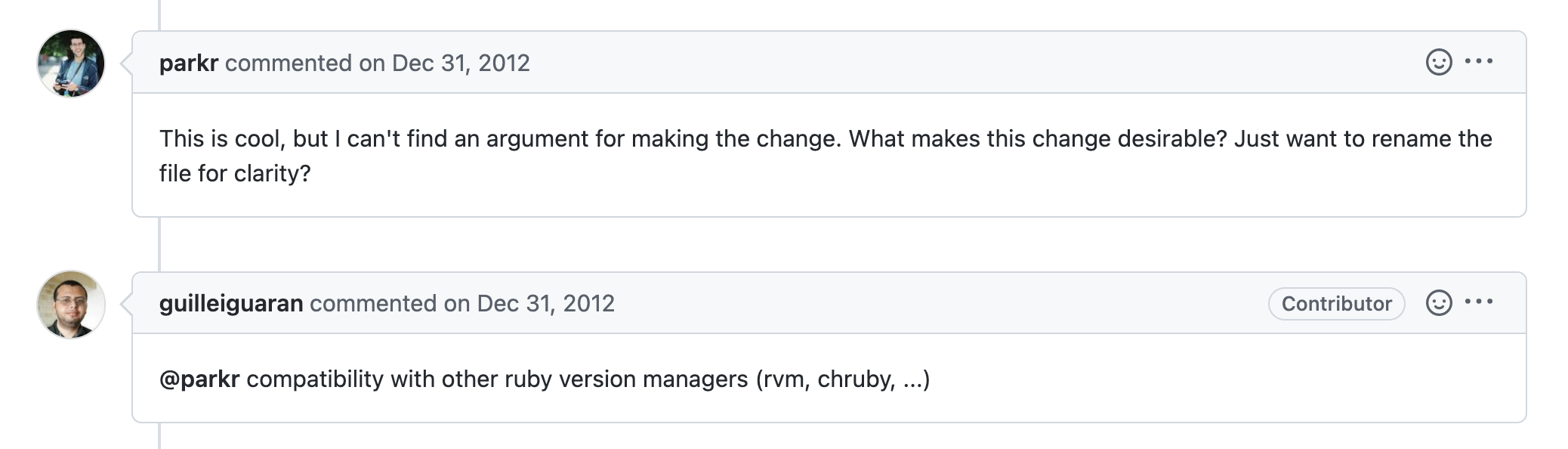

A quick Github search in the RBENV repo for ".rbenv-version" ".ruby-version" (so that I can find PRs which contain both terms) yields 8 results, of which this PR is one. This quote in particular stands out among the comments:

This largely confirms my suspicions about inter-operability.

FWIW, there’s also a comment by Sam Stephenson (the original author and member of the core team) saying:

We will maintain backwards compatibility with existing .rbenv-version files for the foreseeable future.

However, when I search my local version of the codebase for .rbenv-version, nothing is returned, whereas .ruby-version has plenty of references. So I’m guessing that the plan to support the .rbenv-version filename convention must have scrapped at some point.

Please don’t do what I did here

While searching Github for answers to the above, I actually came across a post of mine on this same repository from 2019, where I asked this exact same question!

I only vaguely remember posting this, but I remember the person who answered me was much nicer and more detailed in his answer than he needed to be. In retrospect, I’m a bit embarrassed that I posted this question instead of searching through the git history. If everyone did what I did, open-source maintainers would be overwhelmed and would never get anything done. I definitely don’t recommend that you do what I did- instead, learn from my mistakes. Github is not a 2nd StackOverflow.

It took multiple read-throughs of the issue at hand, spread out over many weeks, along with trial-and-error in the form of experimentation. But eventually I was able to figure this out on my own, without relying on the above post. If you’ve read this far and slogged through all my experiments with me, I’m confident you can do likewise.

Experiment- creating our own shebang

I copy-paste the original ruby-local-exec into a new file in my current directory (remembering to run chmod +x on that new file, or else UNIX won’t recognize or use it). I add a few echo loglines, like so:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "start of ruby-local-exec"

set -e

cwd="$(pwd)"

dirname="${1%/*}"

echo "dirname: $(pwd $dirname)"

cd "$dirname"

export RBENV_VERSION="$(rbenv version-name)"

cd "$cwd"

echo "just before exec in ruby-local-exec"

exec ruby "$@"

I then create a new file called foo, which looks like so:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby-local-exec

puts "Hello world"

The ruby-local-exec shebang is meant to execute Ruby scripts, so my foo script uses Ruby syntax like the puts statement.

The last thing I have to do is update my PATH variable to begin with my current directory, so that UNIX will know where to find the ruby-local-exec file (and therefore, it will know how to run my foo script).

I run the following in my terminal, using our new knowledge of command substitution to update $PATH:

$ PATH="$(pwd):$PATH"

$ which ruby-local-exec

/Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/rbenv/ruby-local-exec

Running which ruby-local-exec shows me that UNIX can now find my ruby-local-exec command in PATH.

Now, when I run ./foo in my terminal, I see:

$ ./foo

start of ruby-local-exec

dirname: /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/

just before exec in ruby-local-exec

Hello world

We see that dirname evaluates to /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/, the directory I’m in on my machine when I run ./foo.

This must mean that, inside the shebang file, the parameter expansion ${1} evaluates to the filename. We can quickly test this by adding a logline to output just that, without any modifications to $1. Above the logline for dirname inside my new shebang, I add:

echo "1: ${1}"

When I re-run, I get:

$ ./foo

start of ruby-local-exec

1: ./foo

dirname: /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/rbenv

just before exec in ruby-local-exec

Hello world

Yep, ${1} inside the shebang evaluated to the filename.

Before moving on, I remove all the loglines I’ve added to ruby-local-exec so far, returning it to its original condition:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

cwd="$(pwd)"

dirname="${1%/*}"

cd "$dirname"

export RBENV_VERSION="$(rbenv version-name)"

cd "$cwd"

exec ruby "$@"

RBENV’s README on Github could help inform that decision.

A couple of possibilities stand out:

Shim Rehashing

Through a process called rehashing, rbenv maintains shims in that directory to match every Ruby command across every installed version of Ruby…

This brings up a good question- we’ve already looked at the shim file itself, but where did that shim file come from? It sounds like that’s part of the “rehashing” process described here, but how does that process work?

From the README:

Choosing the Ruby Version When you execute a shim, rbenv determines which Ruby version to use by reading it from the following sources, in this order:

The RBENV_VERSION environment variable, if specified. You can use the rbenv shell command to set this environment variable in your current shell session.

The first .ruby-version file found by searching the directory of the script you are executing and each of its parent directories until reaching the root of your filesystem.

The first .ruby-version file found by searching the current working directory and each of its parent directories until reaching the root of your filesystem. You can modify the .ruby-version file in the current working directory with the rbenv local command.

The global ~/.rbenv/version file. You can modify this file using the rbenv global command. If the global version file is not present, rbenv assumes you want to use the “system” Ruby—i.e. whatever version would be run if rbenv weren’t in your path.

The process by which RBNV checks which Ruby version to use is something I thought I understood from my last write-up. But it turns out there’s additional logic to do this which doesn’t live in the shim file itself. Maybe I should try to find where that extra logic lives?

Installing Ruby via RBENV

The README also talks about Ruby installation, a process which seems important in the Ruby version management lifecycle:

…

ruby-build, which provides the rbenv install command that simplifies the process of installing new Ruby versions.The

rbenv installcommand doesn’t ship with rbenv out of the box, but is provided by theruby-buildproject.

Why wouldn’t they ship RBENV with rbenv install already included? I’ve used it before and it seems both useful and important enough to include by default. If one doesn’t use RBENV, I don’t know what the process is to wire up a new Ruby version with RBENV once you install it yourself, but I can’t imagine it’s easy.

Shell Integration

From the README:

rbenv initis the only command that crosses the line of loading extra commands into your shell. Coming from RVM, some of you might be opposed to this idea.

Why would someone be opposed to this idea? It seems like there’s something important or controversial here that I don’t fully understand.

RBENV sub-commands

Again from the README:

Like git, the rbenv command delegates to subcommands based on its first argument.

The delegation process seems important since that’s how RBENV executes any and all commands that it exposes. How does this work, under-the-hood?