As usual, we’ll cover the tests first, and the code afterward.

Tests

Happy-path test

After the bats shebang and the loading of test_helper, the first test is:

@test "commands" {

run rbenv-commands

assert_success

assert_line "init"

assert_line "rehash"

assert_line "shell"

refute_line "sh-shell"

assert_line "echo"

}

This is the happy-path test, covering this for loop. The test runs the regular rbenv-commands command, asserts that it was successful, and asserts that certain commands are listed among the output printed to STDOUT.

We also explicitly assert that the line “sh-shell” does not appear in the output. That’s because:

- we generate these command names by fetching any executable file in our

$PATHwhich starts withrbenv - there’s an executable file in our

$PATHnamedrbenv-sh-shell(a filename convention that we covered when discussingrbenv-init) - we don’t want to display the

sh-part of the filename; we only want theshellpart.

Displaying only shell commands

Next test:

@test "commands --sh" {

run rbenv-commands --sh

assert_success

refute_line "init"

assert_line "shell"

}

This test covers this block of code, as well as the 4-line block of code from lines 30-33 (starting here).

In this test, we do the following:

- We run the same command as before, but we pass the

--shflag. - We assert that commands with no “sh-“ prefix in their filenames (such as the

initcommand) are excluded from the printed output. - We also assert that commands with that prefix (such as

shell) are included.

Ensuring that paths with spaces are included

Next test:

@test "commands in path with spaces" {

path="${RBENV_TEST_DIR}/my commands"

cmd="${path}/rbenv-sh-hello"

mkdir -p "$path"

touch "$cmd"

chmod +x "$cmd"

PATH="${path}:$PATH" run rbenv-commands --sh

assert_success

assert_line "hello"

}

To set up this test, we do the following:

- We make a directory whose name includes a space character.

- We make an executable command within that directory called “rbenv-sh-hello”.

- We add that directory name to our

$PATHenvironment variable.

When we run the commands command, we pass the “–sh” flag. We then assert that the command was successful, and that the “sh-“ prefix was removed from the command name before it was printed to STDOUT.

Displaying only non-shell commands

Last test for this command:

@test "commands --no-sh" {

run rbenv-commands --no-sh

assert_success

assert_line "init"

refute_line "shell"

}

This test covers this 4-line block of code, as well as this 4-line block of code. It’s the inverse of the “commands –sh” test:

- We expect commands whose files do not contain the “sh-“ prefix in their name to be printed to STDOUT, and

- We explicitly expect commands which do contain that prefix in their filenames to be excluded from the output.

Let’s move on to the code for the command itself.

Code

First few lines

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Summary: List all available rbenv commands

# Usage: rbenv commands [--sh|--no-sh]

set -e

[ -n "$RBENV_DEBUG" ] && set -x

This is the same beginning as most of the files we’ve encountered so far:

- Shebang

- Comments summarizing the purpose and usage of the command

- Setting the shell options to:

- exit on first error and

- set verbose mode (if the user turns debug mode on).

At some point I may start to skip these lines when we consider new files.

Completions

Next lines of code:

# Provide rbenv completions

if [ "$1" = "--complete" ]; then

echo --sh

echo --no-sh

exit

fi

We’ve seen this before as well, in rbenv-init. If the user types rbenv commands --complete, we echo the two flags shown here (--sh and --no-sh), and then exit the script. This tells the user which flags are accepted with this command.

Note that we did not see this same block of code in rbenv---version. If a command doesn’t include a block of code which checks for --complete, that means we don’t expose a --complete option for that command.

Checking for --sh and --no-sh flags

Next lines of code:

if [ "$1" = "--sh" ]; then

sh=1

shift

elif [ "$1" = "--no-sh" ]; then

nosh=1

shift

fi

If the user has typed rbenv commands --sh, we create a variable named sh and set its value to 1. Otherwise, if the user has typed in --no-sh, we create a variable named nosh and set its value to 1.

We saw these flags when we looked at the tests. Later, we’ll use the sh and nosh variables to decide whether to show only commands which are (or are not) shell-specific.

Setting the paths to iterate over

Next line of code:

IFS=: paths=($PATH)

This sets the IFS environment variable equal to :, and in the same line of code stores the value of $PATH inside the variable paths.

We need to set IFS while running this command because $PATH evaluates to a series of directories delimited by the : character. If we want to take some action on each directory in the $PATH variable, we need a way to split that variable up into discrete directories, rather than treating it all as one big string.

We can verify this with a quick test script, which I named foo:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "size of PATH: ${#PATH[@]}"

IFS=: paths=($PATH)

echo "size of PATH: ${#paths[@]}"

This script does the following:

- We first echo the size of the un-split “$PATH” variable, treating it as an array by adding

[@]at the end.- Remember, the

#char inside the parameter expansion, before your parameter, tells bash to expand the expansion to the size of the parameter.

- Remember, the

- Then we create a new variable,

paths, which is the PATH string split into an array according to the delimiter we set. - We then echo the size of that new variable, again treating it as an array.

When we run this script, we get:

$ ./foo

size of PATH: 1

size of PATH: 20

Because the default delimiter of " " was not found in our first attempt, the interpreter treated our “array” as an array of one giant string. When I changed the delimiter to :, the interpreter split $PATH into 20 discrete directories.

To prove this last statement, I the following code to the end of foo:

for path in "${paths[@]}"; do

echo "$path"

done

When I re-run it, I see the following:

/Users/myusername/.nvm/versions/node/v18.12.1/bin

/Users/myusername/.rbenv/shims

/Users/myusername/.rbenv/bin

/Users/myusername/.yarn/bin

/Users/myusername/.config/yarn/global/node_modules/.bin

/usr/local/lib/ruby/gems/3.1.0

/Users/myusername/.cargo/bin

/usr/local/sbin

/usr/local/opt/ruby/bin

/Users/myusername/.asdf/shims

/Users/myusername/.asdf/bin

/usr/local/sbin

/usr/local/bin

/System/Cryptexes/App/usr/bin

/usr/bin

/bin

/usr/sbin

/sbin

/Library/Apple/usr/bin

/Applications/Postgres.app/Contents/Versions/latest/bin

If we count these entries, we get a total of 20.

Setting the nullglob option

Next line of code:

shopt -s nullglob

When we first learned about importing plugin files, we saw that this line sets the nullglob shell option. The nullglob option, if we recall, “…allows patterns which match no files to expand to a null string, rather than themselves.”

This tells us that we’ll be iterating over a list of paths (probably the paths we just stored in the paths variable).

Iterating over $paths

Next lines:

{ for path in "${paths[@]}"; do

...

done

} | sort | uniq

We iterate over each path in our paths array, and do something with it (to be discussed further down). Then we take the results of that something, and pipe it to sort. We then take the results of that sort operation, and grab just the unique values.

We have to sort first before we can call uniq, because the way that uniq detects duplicates is by whether they are next to each other in the input. For example, it would remove the duplicates in the following input:

Foo

Foo

Bar

…but not from this input:

Foo

Bar

Foo

Next lines of code:

for command in "${path}/rbenv-"*; do

...

done

For each of the paths in our outer for loop, we look for any file beginning with rbenv-, and we assume it’s a command.

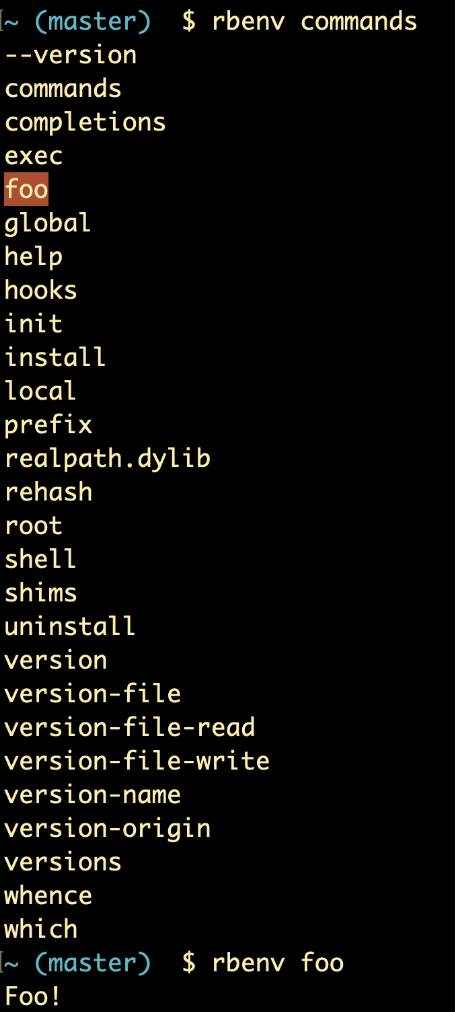

I tested this by doing the following:

- I made a directory in my Home directory called “~/foo”.

- I added this directory to my PATH (

PATH=~/foo:$PATH). - I added a file inside ~/foo called

rbenv-foo, which looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "Foo!"

- I ran

chmod +x ~/foo/rbenv-footo make sure it was executable. - I ran

rbenv commandsand verified thatfoowas one of the commands listed. - I ran

rbenv fooand saw “Foo!” printed out to my screen:

So to sum up the two for loops:

- For each directory in our

$PATHvariable, and - For each file in that directory which starts with

rbenv-

We store the file name using the variable command. The stored value would look something like /usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/1.2.0/libexec/rbenv-completions. Once it’s stored, we then do something with it. That something is discussed below.

Next line of code:

command="${command##*rbenv-}"

According to StackExchange, the ## tells the shell to remove the longest-possible match of the subsequent pattern, in this case *rbenv-. The * means that the pattern can be expanded to include any text ending in rbenv-. So the shell removes the rbenv- text, plus everything before it (i.e. /usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/1.2.0/libexec/).

Therefore, this line takes the value of command defined in the inner for loop and changes it to just the value after the last hyphen. For example, if the previous value of command was /usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/1.2.0/libexec/rbenv-completions, the new value would be simply completions. And if the value was /usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/1.2.0/libexec/rbenv-sh-shell, the new value would be just sh-shell.

Next lines:

if [ -n "$sh" ]; then

if [ "${command:0:3}" = "sh-" ]; then

echo "${command##sh-}"

fi

The outer if conditional checks if the sh variable was set, i.e. if the user passed the --sh flag. If they did, then we only want to echo commands which start with sh-. So we check whether our newly-shortened command variable (i.e. init, global, rehash, etc.) starts with sh-.

If it does, then we print the variable (minus its sh- prefix, using the same strategy we used to shave off the rbenv- from the command variable).

Next lines of code:

elif [ -n "$nosh" ]; then

if [ "${command:0:3}" != "sh-" ]; then

echo "${command##sh-}"

fi

The elif line checks whether the nosh variable was set (i.e. if the user passed the --no-sh flag). If they did, then we check whether our command variable does not begin with sh-. If indeed it does not, then we print the command minus any sh- prefix.

I’m not entirely sure why the ##sh- expansion is needed here, given the if check which wraps the echo statement should have ensured that the command doesn’t have that prefix.

Last lines of code in this file:

else

echo "${command##sh-}"

fi

If the user didn’t pass either the --sh or the --no-sh flag, then we want to echo all commands, whether they start with sh- or not.

That’s all for the commands command. Next we’ll look at the hooks command.