As usual, we’ll do the test first, and the code afterward:

Tests

After the bats shebang and the loading of test_helper, the first block of code is:

create_executable() {

name="${1?}"

shift 1

bin="${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/${RBENV_VERSION}/bin"

mkdir -p "$bin"

{ if [ $# -eq 0 ]; then cat -

else echo "$@"

fi

} | sed -Ee '1s/^ +//' > "${bin}/$name"

chmod +x "${bin}/$name"

}

The create_executable helper function

We start by defining a helper function called create_executable. This function sets a variable named name equal to the first argument, but it looks like something else is happening inside the parameter expansion.

Storing the name of the executable

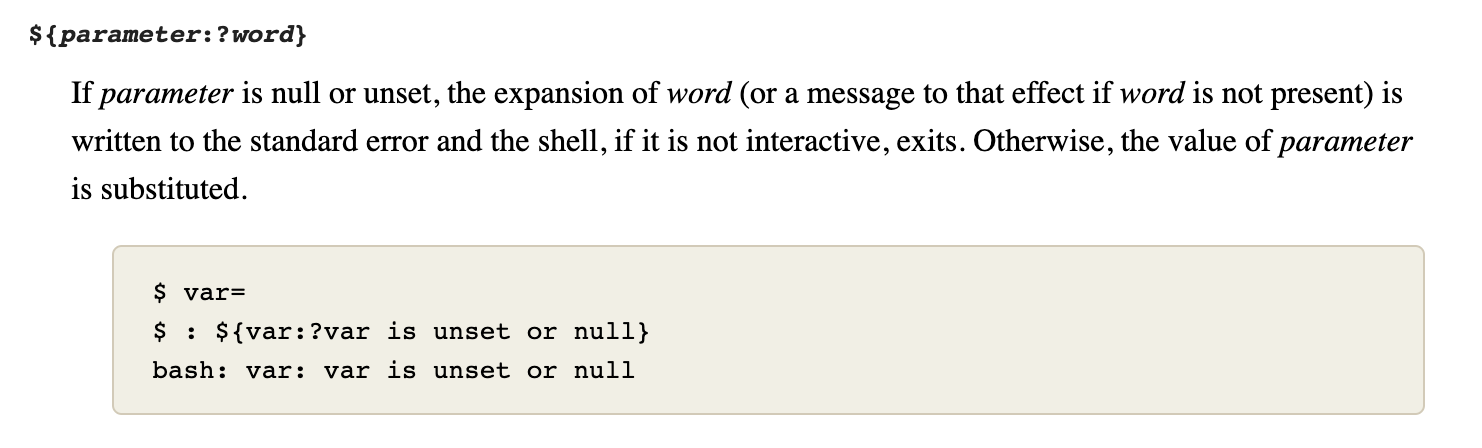

I’m not sure what the question-mark syntax does, so I pull up the bash docs on parameter expansion:

So with the question mark, we get a specific error message saying that the value of parameter (or in our case, "$1") is unset. I try this in my local Bash terminal, and I see the following:

bash-3.2$ unset foo

bash-3.2$ "${foo:?}"

bash: foo: parameter null or not set

So the goal is to show an error if no params are passed to create_executable. If at least one argument is passed, however, we store the first argument as the variable name and shift the arg off the argument list.

Making a directory to store our executable

Next bit of code:

bin="${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/${RBENV_VERSION}/bin"

mkdir -p "$bin"

We create a variable named bin and set its value to the name of a series of directories and subdirectories. We then make a directory with the name stored in bin, using the -p flag to ensure that any intermediary directories which don’t yet exist will be created as well.

Adding content to our executable file

The next bit is long:

{ if [ $# -eq 0 ]; then cat -

else echo "$@"

fi

} | sed -Ee '1s/^ +//' > "${bin}/$name"

Let’s break this into two pieces. The first piece is:

{ if [ $# -eq 0 ]; then cat -

else echo "$@"

fi

}

This half is wrapped in curly braces, meaning we perform it as a single operation and send its contents to the next half. This is called “command grouping” in Bash, and we’ve seen it before (for example, when we defined the abort helper function in libexec/rbenv).

What is the output of the command grouping? We start by invoking $# and checking if it’s equal to 0. Referring back to this line of libexec/rbenv, we recall that $# expands to the number of arguments that were passed to the create_executable function.

So if the # of arguments is equal to 0, then we cat -. Again referring back to that same line of libexec/rbenv, we recall that cat - reads from stdin and redirects its input to stdout.

On the other hand, if the # of arguments is greater than zero, we echo $@ (i.e. we print all the arguments to STDOUT).

So to summarize the output of the command grouping- we either print the content passed from stdin if no arguments were passed to create_executable, or we print the arguments if there were any.

That output gets piped via | to the 2nd half of this block of code. That block is:

sed -Ee '1s/^ +//' > "${bin}/$name"

The sed command

First up- what is sed?

From the man sed page:

SED(1) General Commands Manual SED(1)

NAME

sed – stream editor

SYNOPSIS

sed [-Ealnru] command [-I extension] [-i extension] [file ...]

sed [-Ealnru] [-e command] [-f command_file] [-I extension] [-i extension] [file ...]

DESCRIPTION

The sed utility reads the specified files, or the standard input if no files are specified, modifying the input as specified by a list of commands. The input is then

written to the standard output.

A single command may be specified as the first argument to sed. Multiple commands may be specified by using the -e or -f options. All commands are applied to the input

in the order they are specified regardless of their origin.

The following options are available:

-E Interpret regular expressions as extended (modern) regular expressions rather than basic regular expressions (BRE's). The re_format(7) manual page fully describes

both formats.

-a The files listed as parameters for the "w" functions are created (or truncated) before any processing begins, by default. The -a option causes sed to delay

opening each file until a command containing the related "w" function is applied to a line of input.

-e command

Append the editing commands specified by the command argument to the list of commands.

So the sed command is a string editor command. It takes a block of text and a series of commands, and runs the commands on each line of text from the block.

The -E flag

According to the above man entry, the -E flag tells UNIX to treat the regular expression as a more modern version called an “extended regular expression”, rather than an older version called a “basic regular expression”. According to gnu.org:

Extended regexps are those that egrep accepts; they can be clearer because they usually have fewer backslashes.

The -e flag

According to StackOverflow, the -e flag means we should be able to pass multiple sed commands, chaining them together one after another. However, it looks like we’re only passing one.

Reading the regexp pattern

The one and only regexp that we pass to sed is:

`'1s/^ +//'`

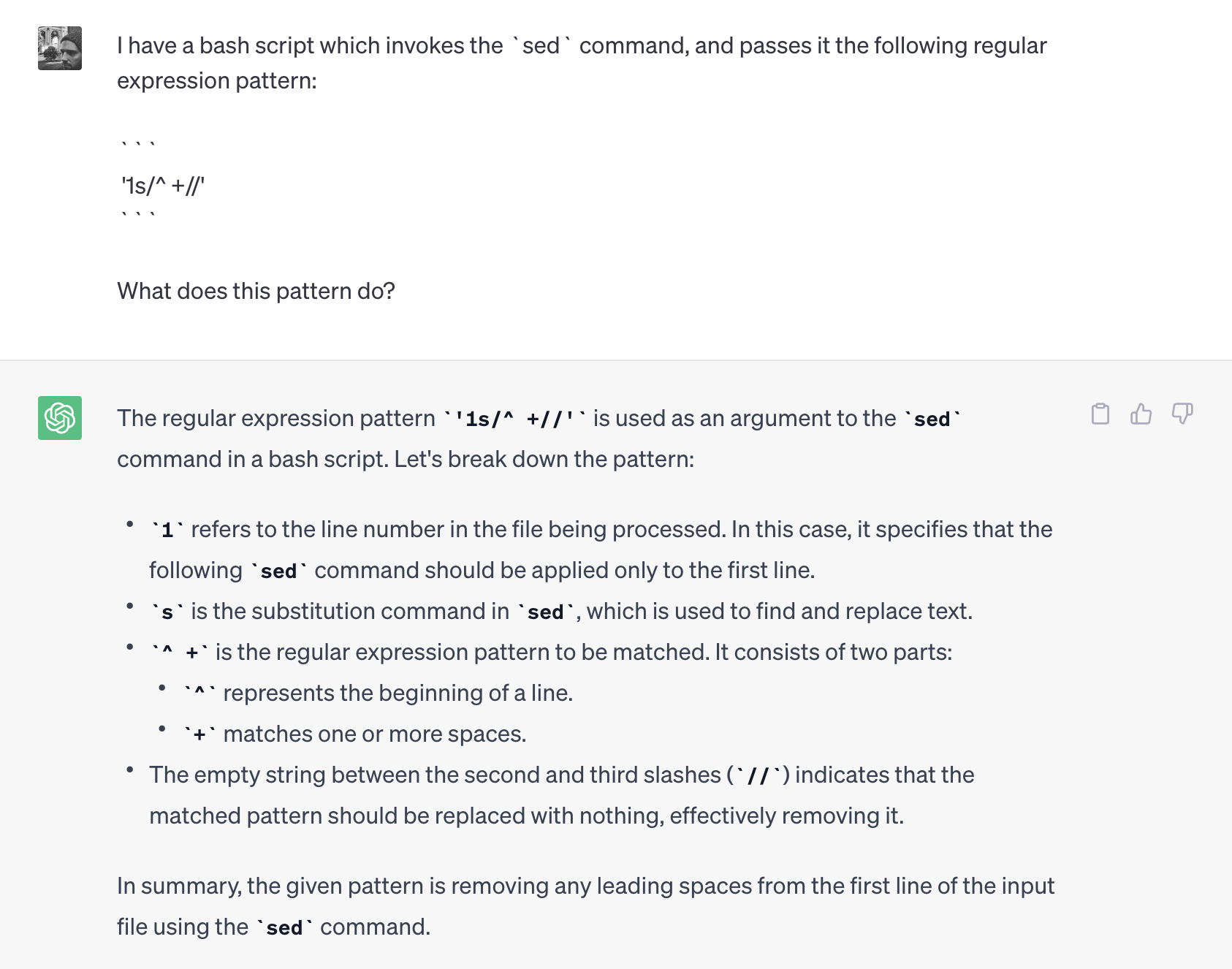

Most regexps that I encounter are very specific to the concise use case they’re being applied toward, making them notoriously hard to Google unless that use case is a very common one among programmers. So in this case, I decide to ask ChatGPT what this pattern does:

From ChatGPT’s answer, we learn that:

1refers to the line number to which we want to apply the regexp pattern. This is confirmed in the documentation forsed, in Section 4.1 titledAddresses overview.s/indicates we’ll be performing a search-and-replace operation, finding some text which matches one pattern and replacing it with something else. In theseddocs, this is covered in section 3.3 (“Thescommand”).- The

^caret character after/tellssedthat the subsequent pattern must start at the beginning of the line of input. The docs confirm this here, in the section “Overview of basic regular expression syntax”.- Although this section deals with basic regular expressions (not extended ones), the section on extended regular expression syntax says that

The only difference between basic and extended regular expressions is in the behavior of a few characters: '?', '+', parentheses, braces ('{}'), and '\|'. - Therefore, we can safely assume that the

^character functions the same in both BREs and EREs.

- Although this section deals with basic regular expressions (not extended ones), the section on extended regular expression syntax says that

" +"(i.e. a space followed by a plus sign) means that we want to match against one or more empty-space characters.- Remember that the

+character is one of the characters whose behavior differs between basic vs. extended regular expressions. - In basic regular expressions, we would add a

\before+if we wanted it to be treated as a special character (i.e. to have the “one or more” meaning). - In extended regular expressions, it’s the opposite- we precede

+with\if we do not want it to be treated as a special character.

- Remember that the

- The

//syntax indicates the content that we want to use to replace the one or more empty spaces that we found.- With no characters in-between the

//, we indicate that we want to replace those empty spaces with nothing. - In other words, we want to delete them.

- With no characters in-between the

To summarize- this command says to look at just line # 1, and delete any spaces at the start of that line (i.e. replace those spaces with the empty string).

Let’s test this to prove to ourselves that the above is correct.

Experiment- removing empty spaces from a line of output

We create a file named “bar” that looks as follows:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo " foo"

echo " foo"

echo " foo"

echo " foo"

echo "bar"

When we chmod +x our bar file, run it, and pipe its output to the same sed command, we get:

$ ./bar | sed -E '1s/^ +//'

foo

foo

foo

foo

bar

As we can see, our empty spaces were removed from the first printed foo output, but not from the subsequent lines.

Sending the output of sed to a file

The output of sed is then sent to a filename that we specify, like so:

> "${bin}/$name"

This means that the output from sed gets written to a file with the name of our name variable, inside the directory with the name of our bin variable.

Making our new file executable

Last line of code in our create_executable function:

chmod +x "${bin}/$name"

We give the current user permission to execute the newly-created file via the chmod +x command.

Invalid version number (provided by an env var)

With the create_executable file out of the way, the next block of code is our first test:

@test "fails with invalid version" {

export RBENV_VERSION="2.0"

run rbenv-exec ruby -v

assert_failure "rbenv: version \`2.0' is not installed (set by RBENV_VERSION environment variable)"

}

This test covers the failure mode of attempting to run a command with a Ruby version that’s not installed:

- We set the

RBENV_VERSIONto “2.0” without having first stubbed out a Ruby installation for version 2.0. - We then run the command “ruby -v” using “rbenv exec”.

- If we had stubbed out v2.0 of Ruby, we could expect to see “2.0” or equivalent in STDOUT.

- However, because we have not done this stubbing, we expect our command to fail with an error message indicating that this Ruby version is not installed.

- Note that the error message also tells us that the invalid version number was provided by the

RBENV_VERSIONenvironment variable.

Invalid version number (provided by a .ruby-version file)

Next test:

@test "fails with invalid version set from file" {

mkdir -p "$RBENV_TEST_DIR"

cd "$RBENV_TEST_DIR"

echo 1.9 > .ruby-version

run rbenv-exec rspec

assert_failure "rbenv: version \`1.9' is not installed (set by $PWD/.ruby-version)"

}

This test is similar to the previous one, except this time we’re setting the incorrect Ruby version via the “.ruby-version” file instead of via an environment variable:

- We make a test directory and

cdinto it. - Inside that test directory, we make a

.rbenv-versionfile and populate it with a version of Ruby that our setup steps did not specifically install. - We run a command via “rbenv exec”.

- This time it’s the “rspec” command, but it doesn’t really matter since either way the Ruby version is checked first.

- We assert that the command failed, and that we received an error message.

- Note that this time, the error message also tells us that the invalid version number was provided by the

.ruby-versionfile, not by an env var.

Printing the possible completions for exec

Next test:

@test "completes with names of executables" {

export RBENV_VERSION="2.0"

create_executable "ruby" "#!/bin/sh"

create_executable "rake" "#!/bin/sh"

rbenv-rehash

run rbenv-completions exec

assert_success

assert_output <<OUT

--help

rake

ruby

OUT

}

This test appears to cover this block of code.

- We specify the Ruby version and make two executables within RBENV’s directory for that version.

- We then run

rbenv rehashto generate the shims for these two new commands, since the completions forexecdepend on which shims exist. - We then run

rbenv completionsfor theexeccommand. - Lastly, we assert that we get both the “–help” completion and the names of the two executables we just installed.

Running a hook and respecting the IFS value

Next test:

@test "carries original IFS within hooks" {

create_hook exec hello.bash <<SH

hellos=(\$(printf "hello\\tugly world\\nagain"))

echo HELLO="\$(printf ":%s" "\${hellos[@]}")"

SH

export RBENV_VERSION=system

IFS=$' \t\n' run rbenv-exec env

assert_success

assert_line "HELLO=:hello:ugly:world:again"

}

We’ve seen a test like this before. The goal is to cover this block of code.

- We create a hook file whose output depends on certain values being set for the internal field separator.

- We then set the Ruby version to the machine’s default version.

- We then run

rbenv execwith a command that we know will be on the user’s machine (theenvcommand, which ships with all Bash terminals). - When we run

rbenv exec, we set the value of the internal field separator to the characters which our hook depends on in order to produce the expected output. - Lastly, we assert that the command was successful and that the output was printed to STDOUT as expected.

It looks like this test was introduced in response to this issue, which reported that a previous PR broke the way that plugins behave.

Forwarding arguments

Next test:

@test "forwards all arguments" {

export RBENV_VERSION="2.0"

create_executable "ruby" <<SH

#!$BASH

echo \$0

for arg; do

# hack to avoid bash builtin echo which can't output '-e'

printf " %s\\n" "\$arg"

done

SH

run rbenv-exec ruby -w "/path to/ruby script.rb" -- extra args

assert_success

assert_output <<OUT

${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/2.0/bin/ruby

-w

/path to/ruby script.rb

--

extra

args

OUT

}

This test covers this line of code. It creates an executable named ruby, whose logic consists of:

- A simplified version of our Bash shebang (using the

$BASHenv var, which evalates to/bin/bashon my machine). - A call to print the “$0” argument, which expands to the name of the script that’s being run

- A loop over all the arguments it receives, printing each one followed by a newline.

We then run rbenv exec with the name of that script, passing arguments which are formatted in many different ways:

- as a flag (

-w) - as a string with spaces in it (in this case, resembling a path to a file)

- as a double-dash (signifying the end of command options)

- as regular arguments (

extraandargs)

Lastly, we assert that the command exited successfully. We then pass a heredoc string to assert_output, ensuring that the arguments printed out the way we expected.

Special test- ensuring rbenv exec respects the ruby -S command

Next test:

@test "supports ruby -S <cmd>" {

export RBENV_VERSION="2.0"

# emulate `ruby -S' behavior

create_executable "ruby" <<SH

#!$BASH

if [[ \$1 == "-S"* ]]; then

found="\$(PATH="\${RUBYPATH:-\$PATH}" which \$2)"

# assert that the found executable has ruby for shebang

if head -n1 "\$found" | grep ruby >/dev/null; then

\$BASH "\$found"

else

echo "ruby: no Ruby script found in input (LoadError)" >&2

exit 1

fi

else

echo 'ruby 2.0 (rbenv test)'

fi

SH

create_executable "rake" <<SH

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

echo hello rake

SH

rbenv-rehash

run ruby -S rake

assert_success "hello rake"

}

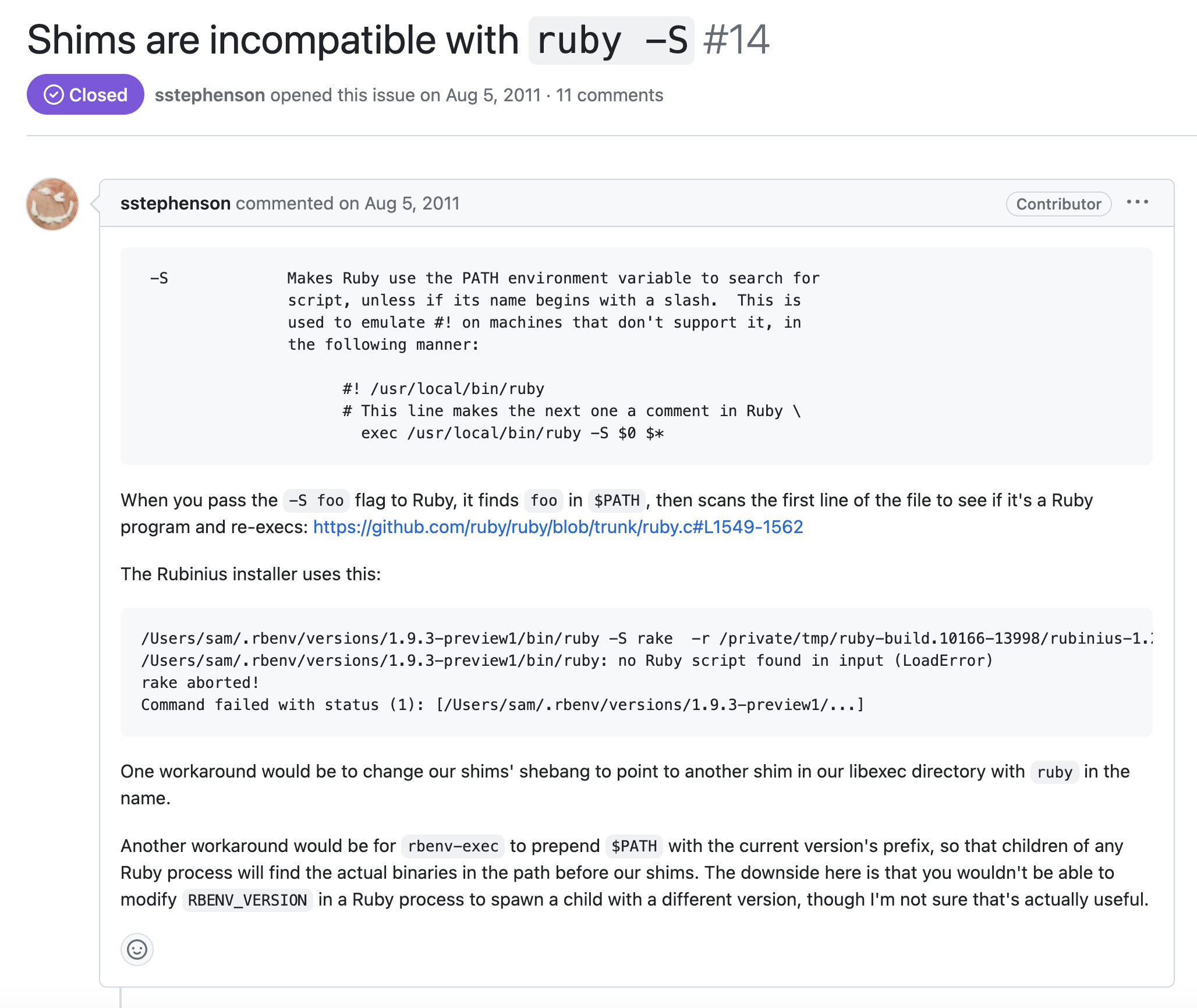

This is a huge test. Before we dive into the code, let’s figure out what Ruby’s -S flag is, and when it’s useful.

When I type man ruby and search for -S, eventually I see the following:

-S Makes Ruby use the PATH environment variable to search for script, unless its name begins with a slash. This is used to emulate #! on

machines that don't support it, in the following manner:

#! /usr/local/bin/ruby

# This line makes the next one a comment in Ruby \

exec /usr/local/bin/ruby -S $0 $*

On some systems $0 does not always contain the full pathname, so you need the -S switch to tell Ruby to search for the script if necessary

(to handle embedded spaces and such). A better construct than $* would be ${1+"$@"}, but it does not work if the script is being

interpreted by csh(1).

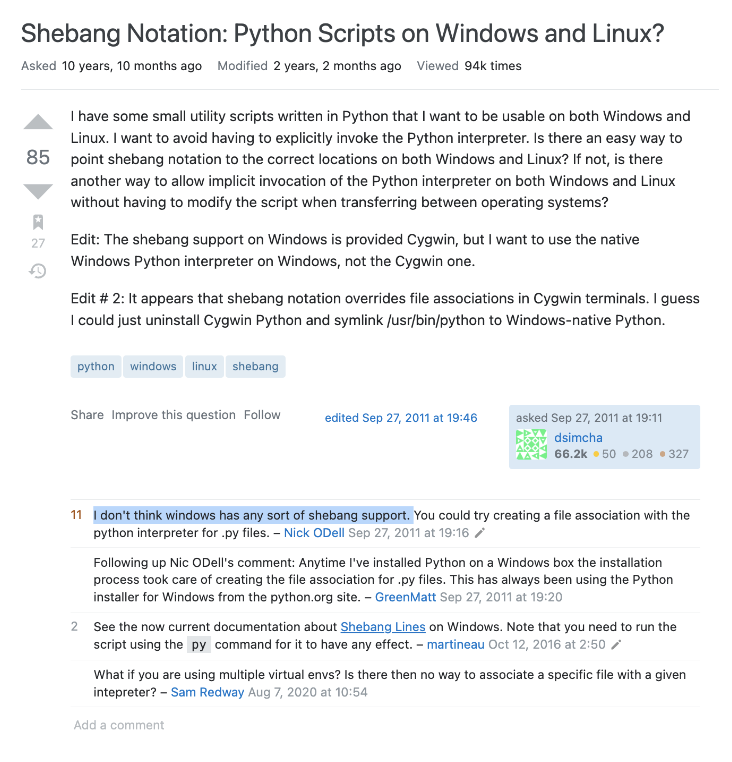

From here we learn that some machines don’t support the use of #! shebangs, and the goal of the -S flag is to be able to overcome this obstacle, enabling the execution of a Ruby script on those machines too.

But how does the former (i.e. the use of -S) lead to the latter (the ability to achieve shebang-like behavior on machines which don’t support shebangs)?

To answer this, I post a StackOverflow question. The gist of the answer is:

- On a machine which does support shebangs:

- The file will be executed as normal, and the shebang will tell Unix to use Ruby to execute the rest of the file.

- Since Ruby is being used to evaluate this file, line 2 will be treated as a comment, since it starts with

#. - Line 3 will also be treated as a comment, since the

\character on line 2 precedes a newline\ncharacter, meaning the newline will be escaped and line 3 will be interpreted as a continuation of line 2. - The rest of the file will be treated as regular Ruby code, as intended.

- On a machine which does not support shebangs:

- Only lines 1 and 2 will be treated as comments.

- Line 3 will be interpreted as executable Bash code, and we call

exec /usr/local/bin/ruby -S $0 $*. - This command uses

execto execute a Ruby interpreter at a specific path. - Because

execis called, this process will be immediately replaced by the new process which calls the Ruby interpreter. - Now that the Ruby interpreter has replaced the original process, lines 1-3 will be interpreted as comments, and the rest of the Ruby code will be evaluated as usual.

Let’s try this with an experiment.

Experiment- the ruby -S flag

I make a file named foo.rb in my directory, and tell it to print the current Ruby version. I also run it with Ruby to make sure it works as expected:

$ echo "puts RUBY_VERSION" > foo.rb

$ ruby foo.rb

2.6.10

Next, I cd up one directory and try running it again, without specifying a relative or absolute filepath. I expect to get an error, and I do:

$ cd ..

$ ruby foo.rb

ruby: No such file or directory -- foo.rb (LoadError)

Lastly, I supply the -S flag and make sure that foo.rb’s directory is in my $PATH:

$ PATH="./impostorsguides.github.io:$PATH" ruby -S foo.rb

2.6.10

This time it works, because I passed the -S flag to ruby and I made sure that the directory for foo.rb is included in $PATH.

Now that I get what -S is and why it’s useful, I’m wondering what prompted this test to be added in the first place.

After a bit of digging, I found this PR with the following description:

The above Github issue reported the following error when trying to install Rubinius:

/Users/sam/.rbenv/versions/1.9.3-preview1/bin/ruby -S rake -r /private/tmp/ruby-build.10166-13998/rubinius-1.2.4/config.rb -r /private/tmp/ruby-build.10166-13998/rubinius-1.2.4/rakelib/ext_helper.rb -r /private/tmp/ruby-build.10166-13998/rubinius-1.2.4/rakelib/dependency_grapher.rb build:mri

/Users/sam/.rbenv/versions/1.9.3-preview1/bin/ruby: no Ruby script found in input (LoadError)

rake aborted!

Command failed with status (1): [/Users/sam/.rbenv/versions/1.9.3-preview1/...]

In particular, the command which triggered the error was:

/Users/sam/.rbenv/versions/1.9.3-preview1/bin/ruby -S rake ...

I gather this was happening because (on a machine using RBENV) the rake executable that was found by ruby -S was the rake shim that RBENV generated. This shim would have had a Bash shebang, not a ruby shebang. This caused Ruby to return the error no Ruby script found in input (LoadError).

We can replicate this error by making a script named foo, containing the following:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo 'Hello world'

If we try to execute this script using ruby, we get the same error:

$ ruby foo

ruby: no Ruby script found in input (LoadError)

So the goal of the test is to ensure that RBENV’s shims to play nice with programs such as Rubinius, which make use of the -S flag.

Now to return to the test code:

export RBENV_VERSION="2.0"

We start by setting RBENV’s Ruby version equal to “2.0”, because the create_executable function depends on that value being set in order to know which directory to store the executable in.

Next:

# emulate `ruby -S' behavior

create_executable "ruby" <<SH

...

SH

We create an executable named “ruby” using our create_executable helper function, and set its contents equal to a heredoc string. The create_executable function will use the RBENV_VERSION value that we just set.

The comment above the function invocation tells us that this executable is meant to emulate the -S behavior of the real ruby command. It seems like the goal is to disregard any behavior not immediately relevant to that flag, in order to act as a minimally-viable test.

The heredoc string representing our pared-down ruby command contains:

#!$BASH

The $ here is not escaped, so $BASH will evaluate to a specific value which represents the path to the Bash executable. On my machine, the above code will look something like:

#!/bin/bash

Next block of code:

if [[ \$1 == "-S"* ]]; then

...

else

echo 'ruby 2.0 (rbenv test)'

fi

If the user’s command starts with -S, we execute the if branch. Otherwise, we execute the else branch.

The else branch is straightforward, so let’s get that out of the way first. If the condition is false, we print the string ruby 2.0 (rbenv test).

On the other hand, if the condition is true:

found="\$(PATH="\${RUBYPATH:-\$PATH}" which \$2)"

Without the escape slashes, this will look like

found="$(PATH="${RUBYPATH:-$PATH}" which $2)"

First, let’s look at the parameter expansion:

"${RUBYPATH:-$PATH}"

If RUBYPATH is set, we’ll use that value. Otherwise, we’ll use PATH.

To find out which value will be used on my machine, I add two echo statements to the test, redirecting the output to a file named results.txt:

...

found="\$(PATH="\${RUBYPATH:-\$PATH}" which \$2)"

echo "RUBYPATH: \$RUBYPATH" >> results.txt

echo "PATH: \$PATH" >> results.txt

# assert that the found executable has ruby for shebang

...

I need the \ escape chars because I want to see what the value of each env var is when the executable is being called.

When I re-run the test and cat results.txt, I see:

$ cat results.txt

RUBYPATH:

PATH: /var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv.skz/root/shims:/Users/myusername/.rbenv/test/libexec:/Users/myusername/.rbenv/test/../libexec:/var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv.skz/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/usr/local/bin

So RUBYPATH is not set, meaning the output of the parameter expansion is the current value of $PATH.

That means our line of code can be simplified to:

found="$(PATH="/var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv.skz/root/shims..." which $2)"

For the sake of clarity, rather than include the entire value of PATH, I added just the first of its directories, followed by ....

Now we have a command substitution, where we call which followed by $2. What is $2 here? I replace my previous echo statements with a new one:

...

found="\$(PATH="\${RUBYPATH:-\$PATH}" which \$2)"

echo "2: \$2" > results.txt

# assert that the found executable has ruby for shebang

...

When I run bats test/exec.bats again and cat results.txt, this time I get:

$ cat results.txt

2: rake

OK, so the following:

found="$(PATH="/var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv.skz/root/shims..." which $2)"

…evaluates to this:

found="$(PATH="/var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv.skz/root/shims..." which rake)"

So we’re setting a certain value for PATH, calling which rake to see where UNIX will find the rake command in PATH, and storing the results of which in a variable named found.

When I echo the value of found, I see it’s equal to:

/var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv/root/versions/2.0/bin/rake

So that’s the value of found.

Now, what is it used for?

if head -n1 "\$found" | grep ruby >/dev/null; then

\$BASH "\$found"

else

echo "ruby: no Ruby script found in input (LoadError)" >&2

exit 1

fi

We pass that filepath represented by the “found” variable to “head -n1”. If we recall from our discussion of greadlink and readlink, calling head -n1 $found means we’re taking the very first line of the contents of the file whose path is stored in found. In other words, the first line of the rake command.

This is the shebang of the rake command. So we’re looking for the string pattern “ruby” in that shebang. We don’t want any output so we redirect the results to /dev/null. We only care about the exit code.

So if the first line of the file (i.e. the shebang) contains the word “ruby”, then we run the following code:

\$BASH "\$found"

On my machine, this evaluates to:

/bin/bash /var/folders/tn/wks_g5zj6sv_6hh0lk6_6gl80000gp/T/rbenv.Eae/root/versions/2.0/bin/rake

So if the condition is shebang is a ruby shebang, we use Bash to call the version of the rake command that we found.

What if that if condition is false?

echo "ruby: no Ruby script found in input (LoadError)" >&2

exit 1

We simply print an error message (ruby: no Ruby script found in input (LoadError)) to STDERR, and exit with a non-zero return code.

So to summarize the ruby test executable:

- We test whether the first arg passed to

rubyis-S. If it is:- We attempt to set

PATHto the value ofRUBYPATH, falling back to the originalPATHvalue ifRUBYPATHis empty. - We then run

whichon the 2nd argument passed toruby(which ends up beingrakewhen the test is run) - We create a variable named

found, and inside it we store the return value ofwhich rake - We check whether the shebang of the file containing our

rakecommand is a Ruby shebang.- If it is, we run it.

- If it isn’t, we

echoan error and exit the executable with a failing status code.

- We attempt to set

- If the first arg passed to

rubyis not-S:- We echo

'ruby 2.0 (rbenv test)'and do nothing else.

- We echo

Next block of code in this test is:

create_executable "rake" <<SH

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

echo hello rake

SH

Here we create a 2nd executable (thankfully a much shorter one) named rake. It just contains a ruby shebang and, surprisingly, an echo command to print the string “hello rake”.

I say “surprisingly” because echo is a shell command, not a ruby command. But our shebang tells the shell to execute this script using ruby. Would that even work?

I make an identical script in my terminal:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

echo hello rake

I chmod +x it and run it, and get the following error:

$ ./bar

Traceback (most recent call last):

./bar:3:in `<main>': undefined local variable or method `rake' for main:Object (NameError)

As I thought, we get a Ruby-flavored error saying that there’s no variable or method named rake, which makes sense because we haven’t wrapped “hello rake” in quotes in our Ruby script. I’m curious if echo would work if we did wrap our string in quotes, so I change the script to this:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

echo "hello rake"

Now when I run it, I get this:

$ ./bar

Traceback (most recent call last):

./bar:3:in `<main>': undefined method `echo' for main:Object (NoMethodError)

This is what I expected- Ruby doesn’t have an echo method, and we get an error. So how is our test passing? Shouldn’t it be getting the same errors I’m seeing above?

Ah, wait a minute. My script is written the same as in the test, but I’m not running it the same way as in the test. The test is running the script with the /bin/sh prefix. I’m running it by itself, without specifying a runner (because I thought I could rely on the shebang).

What happens when I try running it with the /bin/sh command, the same way the test does? I remove the quote marks I just added and return the script to its original state, and run it using the /bin/sh command:

$ /bin/sh bar

hello rake

OK, that worked, because /bin/sh treats any line starting with # as a comment. We could even delete the shebang entirely, and it would still work, because /bin/sh only has one way to run any script it’s given, therefore it doesn’t need a shebang.

As far as I can tell, it’s only when you try to execute a file directly, without using an interpreter such as /bin/sh or ruby, that the shebang is used. Which makes sense, when I think about it.

But then why does the test include the Ruby shebang in an executable that it plans to run with /bin/sh? I know this file is executed by the other file we created here, and I know that file looks at the first line of the rake file to check for a Ruby shebang. But if that shebang isn’t going to be used, then why check for it at all?

Because according to the answer to my earlier StackOverflow question, the real ruby -S command is meant to address the case where a user’s shell doesn’t support shebangs. In that eventuality, the shell will execute the file as a shell script. By running the rake script (containing a ruby shebang) as a shell script via the /bin/sh command, it looks like we’re mimicing the real world usage of -S. When that file is treated as a shell script, the shebang is treated as a comment and ignored, and only the echo hello rake line is executed.

Last block of code for this test:

rbenv-rehash

run ruby -S rake

assert_success "hello rake"

We run rbenv rehash (to make sure the shims for ruby and rake are the first such executables found in our $PATH). We then run the ruby script that we first created, passing the -S flag and the rake argument. Lastly, we assert that the command succeeded, and that “hello rake” was printed to STDOUT.

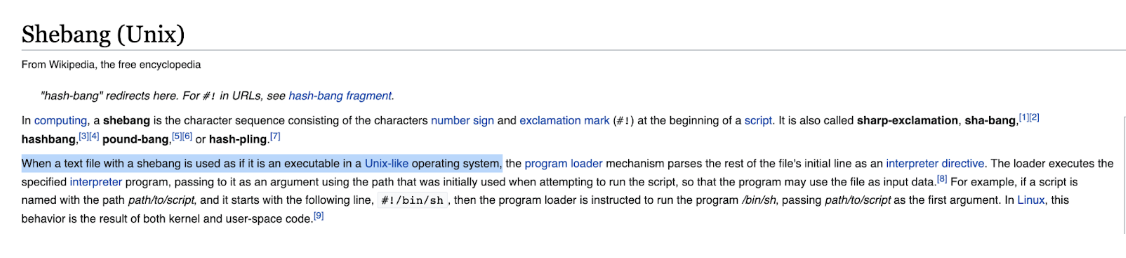

We read earlier that some machines apparently don’t support shebangs. Interesting. I try to look up which ones, starting with Googling “shebang computing”. The first result is a Wikipedia article whose title is “Shebang (Unix)”. That title, plus the sentence in the 2nd paragraph (below), give a clue:

Together, these tell me that one type of machine that wouldn’t support a shebang is a non-Unix system, such as Windows. I find another StackOverflow answer here, which tells me essentially the same thing, when I Google “do shebangs work in windows”:

I feel like that’s a good enough answer for now. Let’s move on to the code.

Code

First few lines of code:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

#

# Summary: Run an executable with the selected Ruby version

#

# Usage: rbenv exec <command> [arg1 arg2...]

#

# Runs an executable by first preparing PATH so that the selected Ruby

# version's `bin' directory is at the front.

#

# For example, if the currently selected Ruby version is 1.9.3-p327:

# rbenv exec bundle install

#

# is equivalent to:

# PATH="$RBENV_ROOT/versions/1.9.3-p327/bin:$PATH" bundle install

set -e

[ -n "$RBENV_DEBUG" ] && set -x

Same deal as before:

- The Bash shebang.

- Comments summarizing what the command is and how to use it.

- Telling bash to exit on the first error.

- Setting “verbose” mode (at least, that’s what I call it) if the user has set the

RBENV_DEBUGenvironment variable.

Providing completions support

Next few lines of code:

# Provide rbenv completions

if [ "$1" = "--complete" ]; then

exec rbenv-shims --short

fi

Here we check whether the user passed the --complete flag as the first argument to rbenv exec. If they did, we run rbenv-shims --short.

This is a different command from what we usually run when the user passes --complete. For instance, here we just echo basic strings when the user passes this flag. I’m curious why we do things differently here.

First of all, what does rbenv exec --complete result in? Let’s run it and find out:

$ rbenv exec --complete

aws-v3.rb

bootsnap

brakeman

bundle

bundle-audit

bundler

bundler-audit

byebug

chromedriver

chromedriver-update

coderay

commonmarker

console

dotenv

elastic_ruby_console

erb

erubis

faker

fission

fluent-post

fog

foreman

gecko_updater

geckodriver

gem

gemoji

geoip

github-markup

github-pages

gli

...

And that’s just the output starting with A through G. It looks like this output is based on certain Ruby dependencies that I’ve previously installed, given the comments we read at the beginning of this file mentioned the specific Ruby version:

# Summary: Run an executable with the selected Ruby version

And judging by the content of the rbenv-shims file (which we’ll get to later), it looks like when the user runs rbenv shims --short, rbenv will print the name of each shim in its shims directory.

Since there’s one shim in that directory for each Ruby gem I have installed, I conclude that we add a shim to this folder whenever we install a Ruby gem which exposes a terminal command. (NOTE- we’ll find out when we read through the rubygems_plugin.rb file that this is correct.)

The reason why we run exec rbenv-shims --short here, and nothing else (i.e. no echo‘ing as with other commands) is that we only expose completions for rbenv exec that correspond to commands you can run using rbenv exec.

Printing help instructions

Next few lines of code:

RBENV_VERSION="$(rbenv-version-name)"

RBENV_COMMAND="$1"

if [ -z "$RBENV_COMMAND" ]; then

rbenv-help --usage exec >&2

exit 1

fi

Here we set the RBENV_VERSION variable equal to the output of the rbenv-version-name command, and we set the RBENV_COMMAND variable equal to the first argument that was passed to rbenv exec.

Then if there was no first argument passed to rbenv exec, we print the rbenv-help script for the exec command (specifically, that script’s output when it receives the --usage flag as an argument), and exit this script.

Setting more environment variables

Next few lines of code:

export RBENV_VERSION

RBENV_COMMAND_PATH="$(rbenv-which "$RBENV_COMMAND")"

RBENV_BIN_PATH="${RBENV_COMMAND_PATH%/*}"

Here we make RBENV_VERSION into an environment variable so that it can be used (presumably) by whichever command is being run by rbenv exec. We also create two new variables (which are not yet exported as env vars):

RBENV_COMMAND_PATH, which we set equal to the output ofrbenv-which $RBENV_COMMAND, andRBENV_BIN_PATH, which we set equal to the value of the previous variable, minus the last/character and anything after it.

When I just now echoed the value of RBENV_BIN_PATH, it came back as /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin. The contents of this directory appears to be the Ruby executable scripts for each of the gems I have installed for my current Ruby version (in this case, 2.7.5, judging by the directory path):

$ ls /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin

aws-v3.rb install_dtrace_on_ubuntu rspec

bootsnap irb rubocop

brakeman jekyll ruby

bundle jmespath.rb ruby-parse

bundle-audit just-the-docs ruby-prof

bundler kramdown ruby-prof-check-trace

bundler-audit ldiff ruby-rewrite

byebug listen safe_yaml

chromedriver mongrel_rpm sass

chromedriver-update newrelic sass-convert

coderay newrelic_cmd scss

commonmarker nokogiri setup

console nrdebug socksify_ruby

dotenv pry spring

elastic_ruby_console puma sprockets

erb pumactl thor

erubis racc tilt

faker racc2y xray_profile_ruby_function_calls.d

fission rackup xray_top_10_busiest_code_path_for_process.d

fluent-post rails xray_top_10_busiest_code_path_on_system.d

fog rake xray_trace_all_custom_ruby_probes.d

foreman rbvmomish xray_trace_all_ruby_probes.d

gecko_updater rdbg xray_trace_memcached.d

geckodriver rdoc xray_trace_mysql.d

gem resque xray_trace_rails_response_times.d

gemoji resque-scheduler y2racc

geoip resque-web yard

github-markup restclient yardoc

github-pages ri yri

gli ri_cal

htmldiff rougify

These are all gems that I’ve got installed, so this must be where RBENV keeps the gems for my current Ruby version.

Fetching the hook paths for the exec command

Next few lines of code:

OLDIFS="$IFS"

IFS=$'\n' scripts=(`rbenv-hooks exec`)

IFS="$OLDIFS"

Here we save the old internal field separator, temporarily set a new separator (the carriage return), create a variable named scripts corresponding to the output of rbenv-hooks exec, and then reset the IFS back to its original value.

I suspect that we change IFS and use the (...) syntax so that the value of scripts is an iterable array of strings. It’s been awhile since we did an experiment, so let’s test this hypothesis by adding some echo statements to the rbenv-exec script.

Experiment- testing the before-and-after length

I update the code to look like so:

...

scripts=(`rbenv-hooks exec`)

echo "original length of output: ${#scripts[@]}" >&2

echo "original items in output: ${scripts[@]}" >&2

OLDIFS="$IFS"

IFS=$'\n' scripts=(`rbenv-hooks exec`)

IFS="$OLDIFS"

for script in "${scripts[@]}"; do

source "$script"

done

echo "new length of output: ${#scripts[@]}" >&2

echo "new items in output: ${scripts[@]}" >&2

...

I also add another (fake) hook to my rbenv.d/exec folder:

$ touch rbenv.d/exec/hello.bash

I do this because, without a 2nd file, both the “before” and “after” lengths printed to the screen will be 1.

Here’s what we get when we run rbenv exec ruby -e 'puts 5' in a new tab:

$ rbenv exec ruby -e 'puts 5'

original length of output: 1

original items in output: /Users/myusername/.rbenv/rbenv.d/exec/gem-rehash.bash

/Users/myusername/.rbenv/rbenv.d/exec/hello.bash

new length of output: 2

new items in output: /Users/myusername/.rbenv/rbenv.d/exec/gem-rehash.bash /Users/myusername/.rbenv/rbenv.d/exec/hello.bash

5

Before we updated IFS, the length of the output was 1, because it just sees 1 large string of concatenated hook paths. Afterward, it was 2, because it’s reading each hook as a separate item in an array.

Sourcing the hooks for exec

Next lines of code:

for script in "${scripts[@]}"; do

source "$script"

done

This for loop iterates over each filepath contained in the scripts variable, and runs source on it.

The reason we had to reset IFS before declaring the scripts variable is so that we could do this iteration.

Conditionally updating $PATH to include our shims

Next lines of code:

shift 1

if [ "$RBENV_VERSION" != "system" ]; then

export PATH="${RBENV_BIN_PATH}:${PATH}"

fi

We shift off the current first-position argument, so that on the last line of code in this file, we can pass the remaining arguments to the command that we exec.

We then prepend the PATH variable with the value of RBENV_BIN_PATH, but only if we’re not using the system version of Ruby which ships with our computer (i.e. if we’re using one of RBENV’s versions instead).

We do this so that, in the subsequent exec command, the first suitable folder in which the shell finds the user’s requested executable is the subfolder of the Ruby version that your configuration has asked RBENV to use. For example, if my current RBENV Ruby version is 2.7.5, RBENV will prepend /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin/ to my path, meaning my shell will search this folder first for any executable with the name of the command I’m trying to run.

I was curious why we have this if check, and after a bit of digging I found this commit. It appears that, if the user is running the system version of Ruby, then their Ruby load path is already part of the overall PATH. And adding it a 2nd time could break things.

Executing the user’s command

Last line of code is:

exec -a "$RBENV_COMMAND" "$RBENV_COMMAND_PATH" "$@"

To see what this command resolves to, I put the following echo statement just above it:

echo "exec -a $RBENV_COMMAND $RBENV_COMMAND_PATH $@"

exec -a "$RBENV_COMMAND" "$RBENV_COMMAND_PATH" "$@"

When I ran rbenv exec ruby -e 'puts 5', I saw the following:

$ rbenv exec ruby -e 'puts 5'

exec -a ruby /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin/ruby -e puts 5

5

As we learned already, exec replaces the shell without creating a new process if command is supplied.

I try looking up the -a flag in the man entry, but it’s confusingly-worded:

The `-a' option means to make set argv[0] of the executed process to NAME.

I look it up here, which says that -a means:

The shell passes name as the zeroth argument to command.

To see how this works, I perform an experiment.

Experiment- Calling exec with the -a flag

I write two scripts:

- one named

foo/bazwhich passes the-aflag:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

exec -a blah ./bar 1 2

- and one named

foo/buzz, which does not

#!/usr/bin/env bash

exec ./bar 1 2

Each of these scripts calls exec on a 3rd script. That foo/bar script looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "Hello world"

echo "0: $0"

echo "1: $1"

echo "2: $2"

If the -a flag causes the value of the 0th argument to change, then I would expect its value to be blah when I run foo/baz, since that’s what I pass in this script.

However, when I run the scripts, the output is the same in both cases:

~/Workspace/OpenSource (master) $ ./baz

Hello world

0: /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/foo/bar

1: 1

2: 2

~/Workspace/OpenSource (master) $ ./buzz

Hello world

0: /Users/myusername/Workspace/OpenSource/foo/bar

1: 1

2: 2

Why is the 0th argument different from what I expected? And why would we want “ruby” as the 0th argument? It seems like exec can handle the full /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin/ruby command just fine, right? I post a question on StackExchange, and soon I get a response.

It seems that some programs change their behavior depending on what the value of $0 is. Also, the -a flag doesn’t work the way I’m calling it, because I’m calling a shell script, not a binary executable. When calling a shell script like so:

$ ./foo

What you’re really doing is calling the program mentioned in the shebang, i.e. /usr/bin/env bash, and passing the shell script name as the argument. In my case, Bash doesn’t care what the 0th argument is, so the behavior is the same in all cases.

We’ve finished reading the code from rbenv-exec. Let’s move on to the next file.