Why I Read Code, Then Write About It

The times when my impostor syndrome is most diminished are the times when I know my set of tools inside and out.

By "tools", I mean languages, frameworks, databases, and any other component of the tech stack in front of me. If I can predict how they'll behave in a given situation, teach how they work to others, and use them in new and novel ways, then my inner critic usually keeps quiet. So it stands to reason that the more of my team's tools I understand, the more confident a developer I'll be.

That's the whole premise of the walk-through I wrote of the RBENV codebase. One day, I found myself asking "What happens when I type bundle install in the terminal and hit Enter?" When I tried to answer that question, the first file I encountered was from RBENV. That's because, in order to manage your Ruby version, RBENV uses shim files for the various commands installed by the user. The file I first encountered was the shim file for the bundle command.

Why I Picked RBENV

In addition to the fact that RBENV was the source of the first file I encountered, I also picked this codebase because it was short enough to seem like a manageable task, and long enough that I thought I'd get a lot of learning out of it.

I could have just as easily picked the Bundle codebase, or Rails, or even Ruby itself. Any of those would have been a perfectly fine choice, and I'll probably move on to one of those next. I even considered punting on RBENV and moving on to Ruby itself, since its internals are more broadly-applicable to my day job than shell scripting is.

In the end, I stuck with RBENV out of a combination of stubbornness and curiosity about how the shell works. I don't regret my choice, since now I have a series of posts which are useful beyond just the Ruby community.

Why I Read The Entire Codebase

At the beginning, it was mostly because I didn't know ahead of time whether a given file was critically important to the overall working of the library. If I read it and it's not important, I've wasted a bit of time but learned something useful (that this thing is not important). If I skip the file and it was important, that inhibits my understanding of whichever file I do end up reading.

Then, as I learned more and more about the codebase, it became a matter of finishing what I started. Yes I'm a bit of a completist, at least with personal projects like this. It means more to me if I can say I read the entire codebase, vs. if I can say I read "most" of it.

There were some parts that I spent more time on than others, of course. And some files I skipped entirely. For example, there's a file in the src/ directory named shobj-conf (no file extension). According to comments at the top of the file, its job is to:

...output a series of variable assignments to be substituted into a Makefile by configure which specify system-dependent information for creating shared objects that may be loaded into bash...

It's almost 600 lines of code long, which isn't by itself a problem. But its purpose is not related to any core part of what RBENV is about. Instead, its purpose is limited to helping optimize the performance of the realpath command, which helps RBENV identify the canonical location of a command in the filesystem. RBENV would function just fine, although maybe a bit slower, using the original implementation of realpath.

Furthermore, this particular file wasn't even written by the core RBENV team. Instead, it's a dependency which was included in the project, and its logic consists of simply declaring certain environment variables, one-by-one, whose values depend on the system architecture of the computer on which it is executed.

For these reasons, covering this file as part of my project seemed like a lot of work for relatively little reward. Anything I'd learn from it would be unrelated to my main goal of learning about RBENV. So I skipped it.

Why I Write About What I Learn

If I can't clearly explain what something does to someone else, it's a sign I don't understand it well enough. So the purpose of writing about the code is to make sure I understand it.

Also, technical blogging frequently results in me learning more than I would have. I call this "the StackOverflow Effect", because when I'm writing out a question on StackOverflow, I frequently am able to come up with an answer before I hit the "Post" button.

The act of writing forces me to examine my own thought process, which has the effect of prompting questions which I wouldn't have thought of via reading alone. This takes me down a rabbit hole which usually results in a more in-depth understanding.

Last but not least- in case it's helpful to someone else! I believe that reading and writing about an open-source codebase is a great way to overcome impostor syndrome. Again, this is doubly true if the codebase you pick is one that your team uses everyday, since it'll make you a more effective team member. But picking any codebase which is maintained by someone who knows something we don't makes us better developers.

Photo Attribution

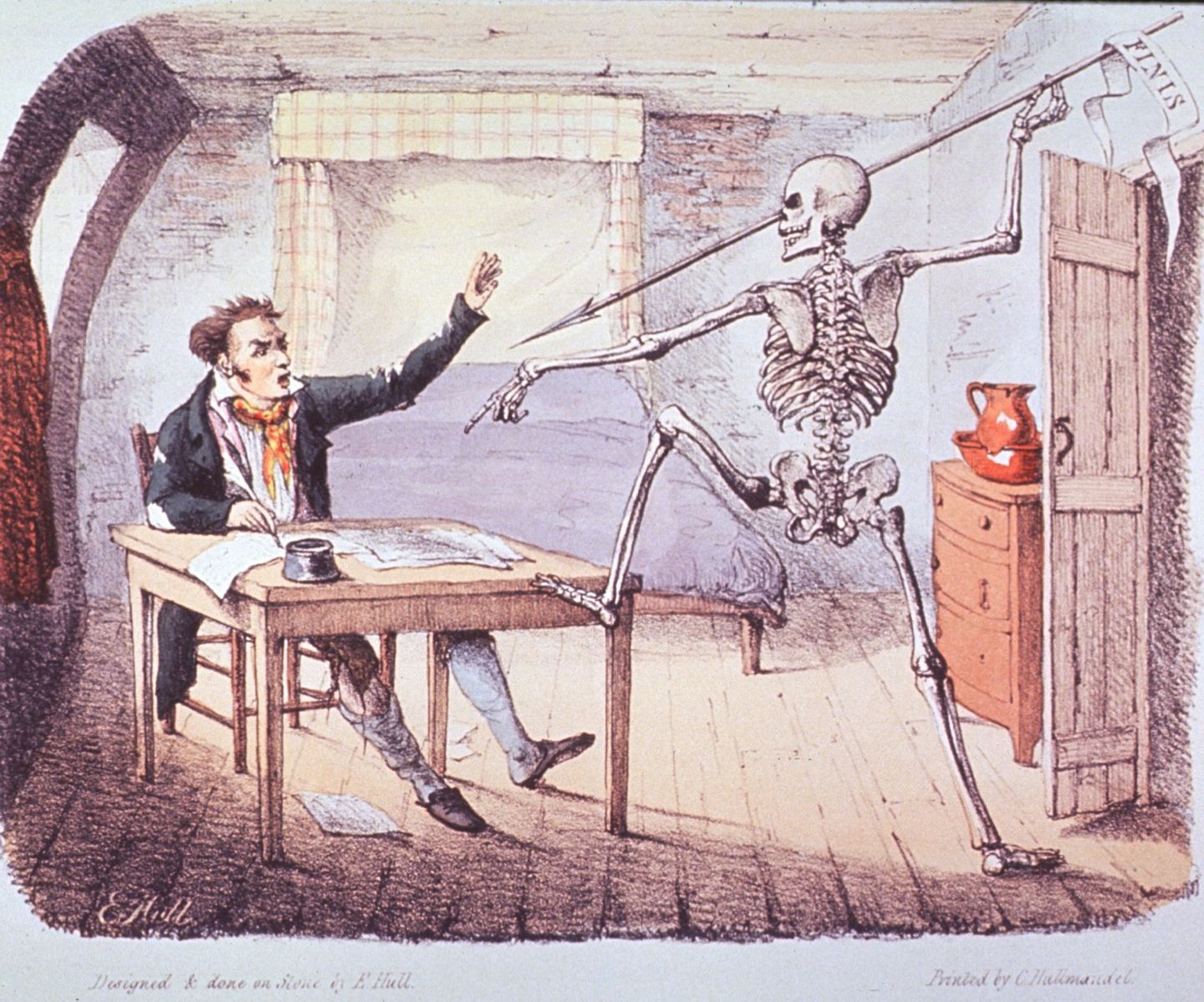

Title: Death found an author writing his life...

Death found an author writing his life.. Designed & done on stone by E. Hull. Printed by C. Hullmandel. London, Dec. 1827.

Author: leiris202

Source: Flickr

License: CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic